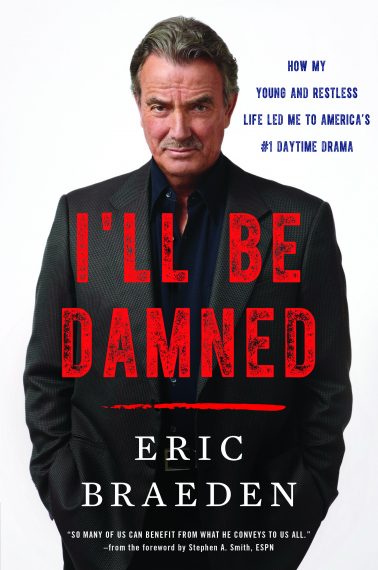

Eric Braeden Previews His Startling New Memoir ‘I’ll Be Damned’

Exclusive

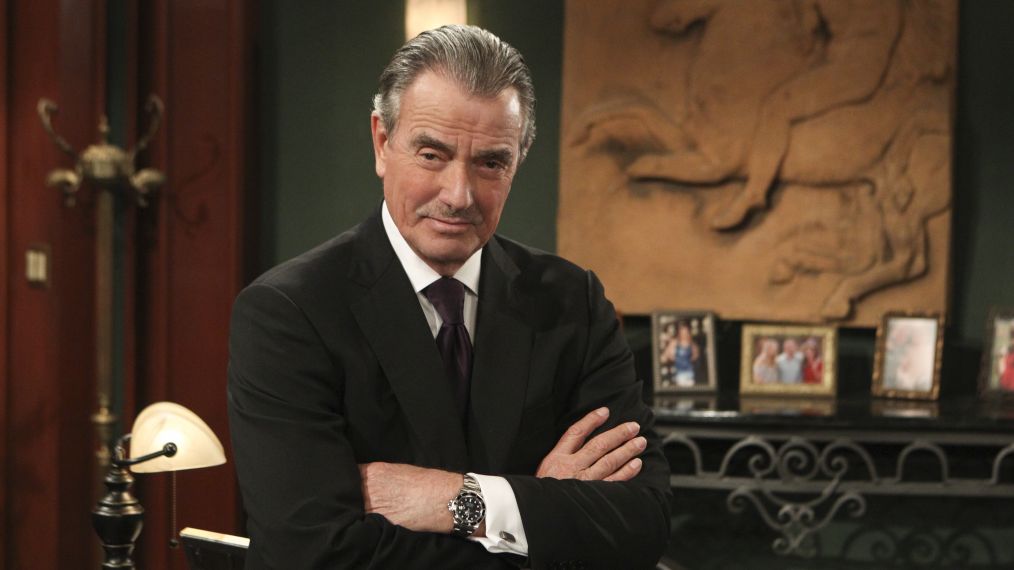

It’s amazing how far a few bucks can take a guy. Eric Braeden came to the United States from his native Germany in 1959, alone and fresh out of high school, with just $50 to his name. Now, as the wily, filthy rich Victor Newman on CBS’s The Young and the Restless, he is the most popular star on daytime’s most popular drama. The Emmy-winning actor shares his immigrant journey in the riveting, often wrenching memoir I’ll Be Damned (HarperCollins), arriving February 7, in which he opens up about a startling family secret—his father was a member of the Nazi Party. It’s a discovery that transformed Braeden, for the better.

Terrific book! And you don’t mess around. Your saga kicks off with you being born in 1941 in a dark basement of a hospital in Kiel, Germany as Allied bombs are exploding all around. The next day, after you were taken home, another round of bombs destroyed the hospital. What is that? Luck? Destiny?

Who can say? But I do feel I grew up with a deep-seated belief that I could overcome anything. That was always a part of me.

And it never failed you? The first work you took in the U.S. when you arrived was cutting up cadavers for medical research. That would have sent most anybody else running home to mommy.

I can’t say I didn’t have my doubts, that I didn’t question what I was thinking coming to this country with nothing and trying to make something of myself. One would be stupid not to question it. [Laughs] One would be a psychopath not to! I guess these things all start in childhood. I grew up one of four brothers who fought all the time. I didn’t take s—t from anyone. There was always an underlying drive to do better, and much of that comes from my growing up [participating] in track and field, where you always strive to improve upon last week’s performance. Never mind today! There is a better tomorrow!

RELATED: The Young and the Restless‘s New Head Writer Sally Sussman Answers Our Burning Questions

One of the most eye-opening revelations in your book is that, even though you were a kid during World War II, you didn’t know about Hitler and his crimes until you were an adult. How do you account for that? After the war, your father even went to prison for a year to be “deNazified” by the Allies, so it’s not as if your family wasn’t drastically affected.

Such things were not discussed. After the war, Germany was intent on rebuilding itself, not looking to the past. It wasn’t talked about at home. I knew nothing of the Holocaust until I went to an L.A. movie theater in 1961 and saw the documentary Mein Kampf, which showed the horrors of the concentration camps. I found it incomprehensible! I loved my father. His death, when I was 12, was the most devastating event of my life. But the sudden knowledge of what his generation had done left me full of shame and rage. And very confused.

So you began investigating his involvement, despite resistance from your mother. Were you afraid of what you’d find?

In my heart, no. I knew my father, who was the mayor of our town, was an honest, decent man and there was never a hint of anti-Semitism in our home. Like most German professionals and government officials of the time, he joined the Nazi Party. It was what one did. But he was not a part of the atrocities. In fact, I found out my eldest brother was approached by the Hitler Youth and my father forbade him to join. So I have come to peace with all that.

Yet that wasn’t enough for you. You went on to establish the German-American Cultural Society to help repair German-Jewish relations. For years you played soccer with the Maccabees, a predominantly Jewish team in L.A. You even met personally with Israeli Prime Minister Shimon Peres. What drove you to do all that?

It’s easy to look back on Hitler with morally dictated hindsight, so it was important for me to study voraciously and understand exactly why my country was bamboozled by that sick son of a bitch. And it came down to two things: The economic insecurity in Germany at the time was of the highest degree, and there was also an intense fear of “the other.” In Hitler’s case, it was fear of Jews. Today, in the U.S., it’s fear of immigrants, of blacks. Like so many of us, I worry about where we are headed. Prejudice is universal. It is a human condition that can only be corrected by communication. I’m sick and tired of people talking past each other. Let’s find out what we have in common as human beings! The fear of “the other” is the worst, most dangerous thing in politics.

We should note that your book is also tons of fun and quite generous with the soap dish—including your first encounter at Y&R with salty grande dame Jeanne Cooper (Katherine), who put her hand on your privates and said, “Let’s see what you’ve got, macho man.” Was that an overenthusiastic welcome or a come-on?

[Laughs] I wasn’t taking any chances. When it happened, I called up [Y&R head writer] Bill Bell and said, “Please, no romantic storylines with that one!”

RELATED: Eileen Davidson Dishes on Her The Young and the Restless and Real Housewives of Beverly Hills Gigs

You don’t leave out your backstage battles at Y&R, including your notorious dressing-room brawl with Peter Bergman (Jack).

I couldn’t say much [about it] because I signed a [non-disclosure] agreement at the time, but I am very glad to say that Peter and I mended fences a long time ago. I respect him enormously, and he and I are good for the show—good together. It was one of those unfortunate things that happened, but I will say that I did not start it. Never have, never will.

And though you don’t name him, a certain Y&R star—who hoped to get you ousted from the show but was himself fired—gets royally scorched in the book.

I debated whether or not to write about that but what the son of a bitch did to me was egregious. It needed to be said. He was a very good actor, but he’s lucky he’s walking in one piece.

You paint an honest picture of soap work—the highs, the lows, the frustrations, the stigma attached to being a soap star.

I came up in the business with people who would say, “Don’t do a soap. It will destroy your career.” Well…here I am. [Laughs] And where are they today?

So no regrets?

None. But there is a sadness that my parents didn’t get to see any of my success. Soaps don’t get much respect within the entertainment industry, and I understand that completely. I really do. One must be down in the trenches to truly appreciate just how hard daytime drama is. It is the hardest work in the business. And it pays. Back in the 1970s, the top salary for guest work in TV was $7500 but when Lew Wasserman, who ran Universal and pretty much ran the TV business, lowered it to $2500, I was furious! You couldn’t make a living on that. It completely eliminated the middle class of working actors. All the money went to the stars and that disproportionate s—t continues to this day. So I said, “F—k this, I’m not going to do it anymore!” And that’s why I eventually succumbed to Y&R. Wasserman had all the power, including the power to change my name. I did my first series, The Rat Patrol [1966-68], under my real name, Hans Gudegast. When I worked for Wasserman in the [1970] film Colossus: The Forbin Project, he said, “No one with a German name will star in my picture.”

Your German nationality proved a problem, as well, when you had a chance to be the next 007.

Sean Connery had quit the franchise and they were getting ready to do Live and Let Die. The producer Cubby Broccoli took me to lunch to talk about my playing James Bond. It was a nice lunch, but he asked if I had a British passport. I said, “No, I have a German passport.” An hour later, my agent was calling to give me Broccoli’s verdict: No one who was not a member of the British Commonwealth would ever play James Bond.

It’s also revealed in I’ll Be Damned that you absolutely hated being cast as John Jacob Astor in Titanic. Explain yourself!

It was my wife, Dale, and my son, Christian, who convinced me to do it. But I was like, “What the f–k am I doing?” It was a great script, but I did not think it was for me. I was miserable all the way to the location in Mexico. I even tried to get off the plane but the flight attendant wouldn’t let me. When I was picked up at the airport, my driver said, referring to [Titanic director] James Cameron, “Are you looking forward to working with the big a–hole?” I was like, “Whaaat?” And the driver says, “Yeah, he’s a real d–k.” I then reported to the wardrobe department and the costumer says, “So are you ready to work with the biggest prick that ever was?” At that point I was ready to run.

But it all worked itself out?

Cameron couldn’t have been nicer and more welcoming and that changed my entire attitude. As a director, he has brass balls. He is a genius, and I say that about very few people in this industry—Meryl Streep, Martin Scorsese and James Cameron, that’s it. At the time there was a lot of talk and a lot of fear that Titanic was going to be a financial disaster that would sink the studio, but I was certain it would be a success, not because of the epic nature of it and the special effects, which were indeed wonderful, but because it was a very expensive soap opera!

Word is, you were reluctant to write this book. How come?

Look, as you have surmised, I have very strong political feelings and very strong feelings about certain people, and I didn’t want to hurt anyone. I was also concerned that my voice, my feelings, wouldn’t translate to the page and that it would all be slightly askew. But working with Lindsay Harrison as my co-writer made all the difference. It has everything to do with her. She gets me. We did a trial chapter and it was so wonderful that it gave me confidence to continue. I didn’t trust that any writer would be able to understand the very German-Jewish issues that are such a big part of my story. I thought, “How can anyone truly get this?” But Lindsay did, magnificently.

There were times you threatened to quit Y&R, especially when contract renegotiations were rough, but you seem to have mellowed. Are you in it for the long haul?

I am a practical man. [Laughs] And no one is waiting for me to star in films. But what makes me stay put more than anything is the audience, which is global. I have strolled through a bazaar in Istanbul and had people come out of the shops shouting “Vic-tor! Vic-tor!” It happens when I walk the streets of Paris. And in Harlem too, only there they say, “Hey, it’s that mean motherf—er Victor Newman! Cold as ice!” The reach of Y&R is extraordinary. People care deeply about the show and our characters, and have done so for decades. In many cases, we are their surrogate family. It’s so easy in this business to become hard and cynical, but meeting the fans is a constant reminder that what we do matters. And, when you realize that, all you can do is stand back in awe and gratitude and say, “I’ll be damned.”