The Beatles: Peter Jackson’s Happy Return to ‘Get Back’

Preview

This is an excerpt from TV Guide Magazine’s The Beatles on TV Special Collector’s Edition, available for order online now at BeatlesonTV.com and for purchase on newsstands nationwide.

Ringo Starr has this dream. It is January 30, 1969, and he is behind the drum set that sits on a wooden platform atop London’s Apple Corps building. Ringo is keeping rhythm for what Rolling Stone magazine has called the greatest live event in rock music history: the Beatles’ rooftop concert, which is the finale to Michael Lindsay-Hogg’s 1970 music documentary Let It Be. The film chronicled the making of that eponymous album; it also offered such a dour look at the bickering bandmates that the group refused to authorize its wide release in the decades that followed.

The rooftop concert—the first live performance by the band in over two years—famously ended abruptly but respectfully, with the police stopping the performance after complaints were lodged by neighbors and the bank next door, saying that the lunchtime tunes were just too loud and disruptive. In Ringo’s dream, however, it all ends with a bigger bang. “In my mind, [the police] come and drag me off the drums,” he has said. “I thought that would’ve made the documentary more interesting.”

While that ending can’t be rewritten, the cheerless legacy of Let It Be can. Peter Jackson’s release of The Beatles: Get Back, is a six-hour re-edit of Lindsay-Hogg’s raw footage. This new edit from the director of the acclaimed Lord of the Rings and Hobbit trilogies reveals a level of energy, camaraderie and collaboration painfully missing from Let It Be. When asked what one should expect from Jackson’s limited series, no less an authority than Starr himself replied, “A lot of joy.” The November 25–27 premiere of The Beatles: Get Back on Disney+ is, as promised for fans, the ultimate Thanksgiving treat—with all the trimmings.

Dark Days

No doubt some will regard the Get Back series as an attempt at revisionist history, and for good reason. No matter what Jackson came up with, it wouldn’t replace Let It Be, which most viewers have seen only in pirated copies found on eBay and elsewhere since the 1980s.

It’s definitely true that Let It Be was recorded while bursting seams were clearly visible in the fabric of the band. The four had coalesced as mates a decade earlier, with the innocent sensibility of kids, but had now grown into married men with interests beyond the band. John Lennon, long the vocal leader of the group, had fallen hard for Yoko Ono, to the point that he bypassed the long-standing rule that wives did not come to the studio during recording hours. While Yoko’s presence was regarded as a distraction—one later made out by the press to be some final blow to the band—the greater truth was each player had plans beyond the Beatles.

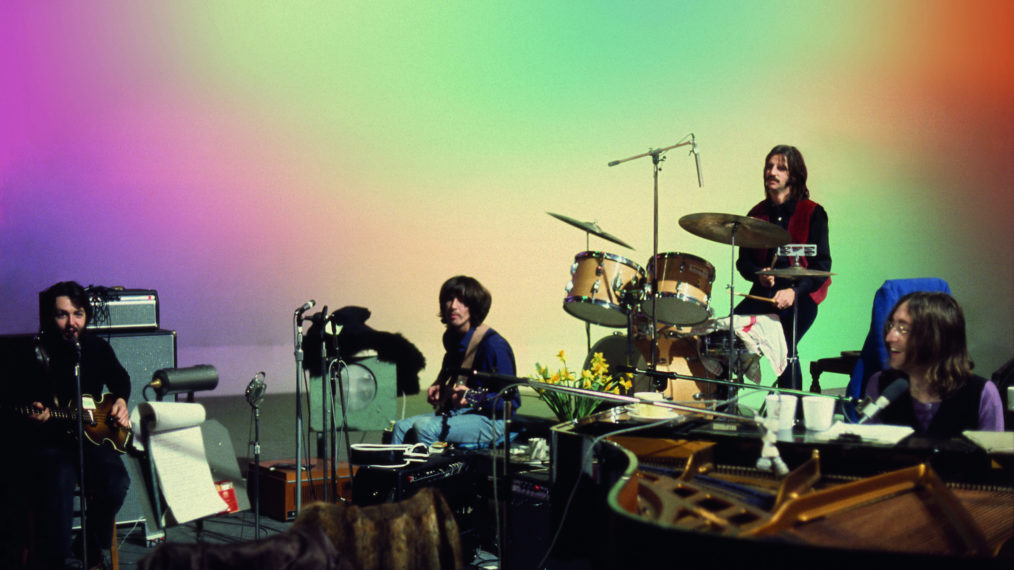

Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

The Let It Be album had initially been embraced as a “return to roots,” as suggested by Paul McCartney. The band had previously slogged through recording The Beatles (aka the White Album), during which the mates argued constantly. Growing pains were taking a toll; McCartney and Lennon each criticized the other’s songs, the former laced into Starr for his drumming on certain tunes (leading Ringo to leave the studio for a time) and myriad disagreements led to the entire band playing together on only half the songs on the double album. Months later, Let It Be was seen by the band as a chance to jam together more, to regroup and rediscover their collective mojo, even as business tensions about the new Apple Corps company persisted.

The idea for Let It Be was to work toward doing a live show (with a location to be named later) and, therefore, create songs that didn’t need all the complicated, sound-shifting overdubbing the band had grown used to doing in the studio. It was also suggested that they invite a film crew in to capture the magic of their record-making process and turn it into a television special to accompany the concert. Filming and rehearsing both began at Twickenham Studios in London on January 2, 1969, the site chosen because Starr was also shooting the Peter Sellers film The Magic Christian there.

However, the unfamiliar surroundings away from their regular studio, the spartan-looking set at Twickenham, a daily recording schedule that began earlier than normal and the constant presence of cameras made for strained creative collaboration. Arguments sprang up—most famously between McCartney and lead guitarist George Harrison, over the way the latter played on the song “Two of Us”—and the band members would later recall the shooting days at Twickenham as being terrible. Lennon called them “the most miserable sessions on earth.” Harrison himself walked out and returned a few days later only after the band agreed to move back to their home studio at Apple, and if the plan for an elaborate concert was dropped. He came back into the fold, and filming concluded at the end of January 1969 with the more impulsively planned rooftop show.

A rough edit of the film was shown to the Beatles that July, and cuts were made, limiting the amount of screen time John and Yoko received; also, no reference was made to Harrison leaving the group. The film’s title was later changed from Get Back to Let It Be, and it was released in theaters mid-May 1970. McCartney’s screen time clearly dwarfs that of his bandmates, and a scene of dialogue late in the film between him and Lennon—which actually plays as a monologue to an entirely silent Lennon—seems to suggest the rooftop concert is Paul’s idea alone. The New Yorker, appearing to sum up a degree of sentiment, said Let It Be was both “bad” and “touching” in that it showed the breaking apart of a “once apparently ageless family of siblings.”

A Different Take

While there’s no arguing with all that history, many have since then offered reappraisals of those divisive days. It’s true Let It Be looks dour and grainy, but a transfer from 16mm to 35mm (to make it more suitable for theatrical release) didn’t help. And it’s true all four Beatles look as though they’d rather have been anywhere else during the filming (Ringo in particular), but it turns out that plenty of film was left on the cutting room floor—enough to create an entirely different mood.

That mood has been acknowledged for years. As Steve Matteo reports in the book Let It Be, observers of the sessions at Twickenham paint a startlingly different picture. One among them was Anthony Richmond, cinematographer for Let It Be, who said of the sessions, “There are moments where they’re having a rough time, but you could also see moments where they’re just mucking about and having a good time and laughing and joking, and Lennon’s dancing. I can only remember it as a good time.” The album’s engineer, Glyn Johns, has also said of those days, “John Lennon only had to walk in a room and I’d just crack up. Their whole mood was wonderful.”

Courtesy of Apple Corps Ltd.

That none of the Beatles later recalled this is no surprise. In the 15 months between filming Let It Be and the movie’s release, the band recorded what turned out to be their famed swan song, Abbey Road, and then closed up shop for good. Let It Be, the film—recorded a year prior—seemed like an up-to-date document of their ugly split.

All that began to change a few years ago, when Peter Jackson was asked by the folks at Apple Corps if he’d rework some archival video for a planned traveling Beatles exhibition. Jackson had managed a technological miracle for his 2018 documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, which seemed to bring incredible color vibrancy to footage of World War I soldiers.

When Jackson—a huge Beatles fan—then asked Apple execs about Let It Be, they said a new documentary was being planned based on all the accrued footage, adding that the original director of the project had dropped out. Jackson immediately volunteered for the post, but he wanted to see what amounted to about 60 hours of previously unseen film.

He took all the reels back home to New Zealand. “I was waiting for it to go bad,” the director recently told Vanity Fair, “[but] what I found is that I was laughing continuously. I was laughing and laughing and I didn’t stop.”

That was news to McCartney. When Jackson visited him backstage at a 2017 concert, he promised the ex-Beatle—who still carried lots of guilt that he was responsible for the end of the band—that the video actually told a lively and funny tale of four friends who still loved each other and were eager to work together. “He has never seen this stuff, even though he lived through it,” Jackson has said. “It’s a long time ago, and subsequent events, I think, muddied the whole memory of this thing.”

Gift for Fans

The Beatles faithful will see it set right once they watch Get Back. “This movie will be the ultimate fly-on-the-wall experience that Beatles fans have long dreamt about,” Jackson said in 2019. “We get to sit in the studio watching these four friends make great music together…creating now-classic songs from scratch. It’s not only fascinating—it’s funny, uplifting and surprisingly intimate.”

While Jackson added, “Sure, there’s moments of drama, but none of the discord this project has long been associated with,” it does leave even the least cynical fan recalling the Harrison-McCartney feud in Let It Be. “I always hear myself annoying you,” McCartney said during the early-filming confrontation while trying to show Harrison a guitar part. “I don’t mind. I’ll play whatever you want me to play, or I won’t play at all if you don’t want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you, I’ll do it,” a frustrated Harrison replied. Jackson couldn’t fix that with editing, could he?

In fact, he could. While Jackson said Get Back would amazingly pick up none of the footage from Let It Be, “The one area we did break that rule is that little exchange between Paul and George,” he recently told GQ. “I didn’t want to be accused of sanitizing the film by not having that. But we’ve given people the context for the interaction by showing the full six-minute conversation. It no longer feels like an argument [or] Paul getting on George’s nerves. You understand what Paul’s trying to achieve. You understand where George is coming from. And the whole thing actually makes sense.”

A big treat for fans is the unvarnished rapport that clearly still existed for the Beatles during these sessions, including instances of musical collaboration, laughing conversations between Yoko and Paul’s wife Linda, plenty of horseplay (especially, as it turns out, with Lennon), laughs and gags. But arguably nothing is more poignant than McCartney unveiling a brand-new song he’d only just written called “Let It Be,” with George simply suggesting that it might be improved with a little piano intro. “What, like this?” McCartney asked before launching into one of the most famous intros in rock music history.

Topping It All Off

Also ready for revision was the tale of how the rooftop concert came to be. As Starr has long maintained, the band was considering outlandish options for what would be their final live spot. Perhaps “Hawaii in a crater, or the pyramids, Mount Everest, whatever, and then [we decided], ‘Sod it, let’s just do it on the roof.’”

Starr, who loved what Jackson showed him—as did George Harrison’s widow Olivia, and Yoko—was also pleased by new footage that showed his influence on the concert in the first place. While it was already planned, the Beatles were seemingly nervous about going through with it; George was especially hesitant. “So, Paul says, ‘Who wants to play live?’ and I go, ‘I do!’ And they’ve got footage of that. Of course, everybody wanted to in the end,” Ringo said in a 2019 SiriusXM interview. So, upstairs they went…and the rest will be history all over again.

“We never saw that [great] footage when Michael Lindsay-Hogg put his film together,” Ringo continued. “They stuck to those seconds of argument; but there was a lot of joy, and I think Peter shows that…. This one is more expressive and more like we were.” And, speaking of the rooftop concert, but with words that could refer to Jackson’s film in general, Ringo said, “That was us live again.”

The Set List

The final episode of Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back concludes with the Fab Four on the roof of 3 Savile Row, London, location of Apple Corps, where their famed rooftop concert took place. Anyone familiar with the Let It Be movie will be surprised to see that the band actually made the performance into a kind of rehearsal, running through a total of nine takes of five Beatles songs. All five songs are Lennon-McCartney compositions, and total runtime for the concert—which Jackson’s series shows in its entirety—is 42 minutes. It would have been longer, of course, had the police not interrupted. But it did end humorously, with Lennon quipping, “I’d like to say thank you on behalf of the group and ourselves and I hope we passed the audition.” Here are the songs played that day, in order:

“Get Back” (Take One)

“Get Back” (Take Two)

“Don’t Let Me Down” (Take One)

“I’ve Got a Feeling” (Take One)

“One After 909”

“Dig a Pony”

“I’ve Got a Feeling” (Take Two)

“Don’t Let Me Down” (Take Two)

“Get Back” (Take Three)

We Can Work It Out

While in the studio that January, the Beatles worked on dozens of songs they considered for the Let It Be album that was ultimately produced by Phil Spector. Along with jamming on classics they loved (“Bésame Mucho” and “Kansas City,” for instance), they also tried out “I Want You (She’s So Heavy)” and “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window,” both of which ended up on Abbey Road; Lennon solo works “Gimme Some Truth” and an early version of “Jealous Guy”; and tunes that would end up on Harrison’s first solo effort, All Things Must Pass, including the title song and “Isn’t It a Pity.” But these songs are the ones seen in the Let It Be film in the order they were first played:

“Don’t Let Me Down”

“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer”

“Two of Us”

“I’ve Got a Feeling”

“Oh! Darling”

“One After 909”

“Across the Universe”

“Dig a Pony”

“I Me Mine”

“For You Blue”

“Octopus’s Garden”

“The Long and Winding Road”

“Dig It”

“Let It Be”

“Get Back”

The Beatles: Get Back, Documentary Premiere, November 25–27, Disney+