‘Rectify’ Finale: Creator Ray McKinnon on the Show’s ‘Psychological and Behavioral’ Storytelling

Rectify, Sundance TV’s Southern gothic drama about a man released from prison after serving 19 years on death row for a crime he may not have committed, concludes this week and there are plenty of lingering questions. Uncertainty has been a bit part of the show’s atmosphere from the beginning. What role did Daniel (Aden Young) really play in the rape and murder of his high school girlfriend? After nearly two decades of isolation, even Daniel himself is no longer sure what really happened.

But as its fourth and final season closes in on the end, the show seems poised to give fans something they may not have expected: answers. Still, whatever answers we get, one question remains: How did creator Ray McKinnon get so good at what he does? TV Insider chatted with McKinnon (above, with Abigail Spencer) last month as he put the finishing touches on the series’s final episodes.

RELATED: Rectify: Exiled Daniel Heads to Nashville as the Final Season Begins

When you look back, what are your thoughts about this story that you’ve told over the last four seasons?

The whole reason for telling the story is to experience it in a way that fiction can. You can make very small moments seem like big things and big things seem like small moments. So there’s the micro of Daniel’s life on a second-to-second, day-to-day basis versus the macro of the story, which is: Can a guy who’s been in a box for 20 years survive in a world that there is no box, there are no boundaries? Can he overcome his own internal boundaries to transform himself and become a person who can find some reason for being in the world? That was always part of the impetus for me wanting to write this story, to understand him better, but also to see if he could survive and perhaps thrive in the real world. That’s always been the journey and part of the drama, I suppose, of the journey are the extreme highs and lows that someone like him would experience in the world.

Rectify has always felt like a very impressionistic show. It’s more concerned with mood and imagery. Why did you choose to tell this story in this particular way?

If I were a person who thought more in plot driven terms, I’d probably have a lot more money by now. I can only seem to think in terms of stories that very few people ever want to see. My whole thing has always been I want to tell a story that I myself would like to see and that’s always what I’ve been driven by. In the first season, you don’t know if anybody’s gonna want to see what you want to see. I made the story that I wanted to see, but whether anybody else would be attracted to it, you don’t know. The gratifying part of that was there are people who have been drawn to this story in the way that I wanted to see it, and therefore in the way that I told it. I don’t think I thought consciously about telling a story that has very little plot, because for me there was a lot of plot, but it was more psychological and behavioral, I guess.

This show’s perspective seems to indicate that giving the audience a clear cut, definitive answer about what happened between Daniel and Hannah 19 years ago isn’t really a priority.

Well first, I read a disturbing statistic recently and in some major cities around the country, 50 percent or less of murders are actually solved. I think in storytelling, first of all you think about the families of the victim and the fact that they may never know. Many don’t ever know, so they have to figure out how to go on with their lives without that kind of closure, and that’s a story unto itself. But originally I was drawn to this story because I was curious about the people that had been released from death row or life without parole because of DNA evidence that proved that they weren’t the ones that committed the crime.

And so there’s a lot of ramifications of that. There’s a lot of questions about that. One is why do people get wrongly convicted? And one of the reasons is society really wants to know the answer. They need the answer and prosecution, if they’re not psychopaths or narcissists, they get caught up with this societal pressure of deliver us the killer. They figure out this narrative and try to find someone that will fit that narrative and they themselves believe that this person killed the person who was murdered. So that interested me because that’s what happens in society.

What also interests me, what also is intriguing is we generally tell stories because it makes sense of our world, in some way it gives us a dénouement, a closure to that story and that’s part of the reason we like stories. In real life sometimes there is no dénouement. It’s just, life goes on. These were ideas and philosophies that interested me years ago when I wrote [Rectify].

RELATED: Rectify: Janet Is Determined to Reunite With Daniel (VIDEO)

Everything about this show, everything about the story and the way you told it, resists that real life compulsion to know, which as you said can be really dangerous…

Well, we live in a world that’s chaotic and where events happen seemingly without reason and as human beings we try to create a rationality behind our existence and that creates law and order and closure and resolution that sometimes are not possible, and I suppose I wanted to reflect on how human beings deal with a chaotic world that is not always just and certainly isn’t black and white.

Do you ever feel any tension or conflict between what you as a person want for Daniel and what you as a storyteller feel is right for his story, for the truth of this story? And how do you handle that?

Interesting question. I don’t think I have ever thought of a character that way consciously—what I would want for him or her personally. I know I contemplated how to leave Daniel at the end of the series but always in service of what I thought was right for the story. Now that that is proposed… Yes, I personally would want Daniel to have a long, intermittently happy life. I just don’t know that he will.

Rectify, Series finale, Wednesday, Dec. 14, 10/9c, SundanceTV

From TV Guide Magazine

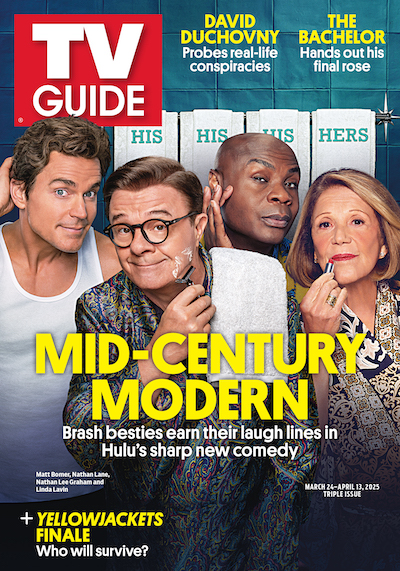

How Hulu's 'Mid-Century Modern' Is a 'Golden Girls' for Our Times

Settle in for some older and bolder laughs with the BFFs of a certain age in the new comedy starring Nathan Lane, Matt Bomer, and Nathan Lee Graham. Read the story now on TV Insider.