‘I Love You, You Hate Me’: Creatives Believe Barney Bashing May Have Shaped Our Future

Q&A

Barney & Friends was a 90s cultural phenomenon that advocated for peace, togetherness, and love. At first, this was widely embraced, but eventually, it turned to hate during the dawn of the internet and trash TV. Some people thought his songs were annoying, and that’s understandable. But others hated the purple dinosaur so much that they became violent or made it their personality to hate him. There was even a mock religious organization called the Jihad to Destroy Barney.

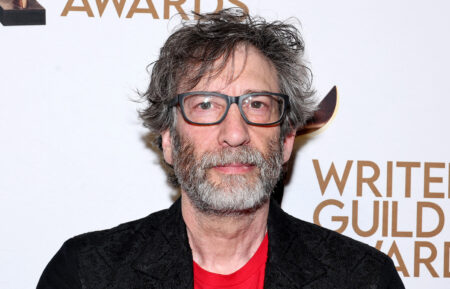

Director Tommy Avallone and Joel Chiodi, Executive Producer and Head of Documentaries at Scout Productions, delve deep into the cultural impact of Barney the Dinosaur with their two-part Peacock documentary I Love You, You Hate Me. But they also get into the concept building and production of the character, as well as how it affected the actors, creatives, and their families.

What made you gravitate towards Barney and this documentary at large?

Tommy Avallone: Yeah, I just saw this old newscast from 1993. It was about the University of Nebraska. It was a Barney bashing event where these college kids were bashing Barney. And at the end of the broadcast, the news guy goes, “that’s the future of our country right there.” And it’s like, oh, well, we’re living in that future now, there is a good level of hate. I wonder if you could tell a story about where hate comes from and love and hate, but told through the eyes of Barney the Dinosaur. Here’s a character that just wanted to teach you how to love. But we all kind of collectively hated him. It was never like, “Hey, let’s do a documentary on Barney.” But we just saw Barney as a perfect avenue to kind of talk about where hate comes from.

Joel Chiodi: One of the key differences with Barney is I think he blows up the masculine tropes of what you think a dinosaur is. One of the things I’ve said throughout this production is, as recently as this summer, there’s been a new Jurassic Park sequel. Jurassic Park came up the same year as Barney, it’s a beloved franchise, and it opens to hundreds of millions of dollars.

And yet this innocuous kids show with a dinosaur that doesn’t have the same, you know, masculine ideals, from his hands to his face, [that] can be triggering to people. The same people who are concerned about a black Ariel in The Little Mermaid. I think these things blow up our ideas about things and make people really defensive. I think that is a key piece of this.

Steve Burns is the closest thing people have had to Barney since Barney but somehow avoided all the hate. Why do you think that is?

Avallone: Barney got a lot of urban legends. And so did Steve. You know, people thought Steve died of heroin or died of a car crash. There are a lot of rumors about the death of Steve, you know? And in the second episode, he talks about that, where it’s like, if you think like, urban legends about Steve from Blue’s Clues dying or whatever, but it personally affected him. He was upset, like, is this the personal preference of everyone? Would everyone rather see me dead?” It’s very upsetting in that way. But Steve does mention how Barney is this character that always smiles. We have a couple clips in the Barney Bible in the movie where it talks about what Barney is when he’s sad, happy, angry, confused, and it’s all the same face because it’s all he does. His face doesn’t move. Steve, on the other hand, is a human being with real emotions. And there’s a different way to connect to that as opposed to just a purple dinosaur that just ear-to-ear smiles, you know?

Peacock

The 90s were a strange time for a child. I remember vividly checking out Maury at 10 am when I stayed home from school and then changing to Nick Jr at 11. Do you think that parallel is reflective of the turning point in society?

Avallone: Everything that we know as normal now was starting there. Daytime TV, where you talk about that, we mentioned Jerry Springer in ours, or the very beginning of the internet as well. All these things just started during that time. And 30 years later, we’re kind of living in the aftermath of all that, the beginning of the internet, beginning of like, shows like Jerry Springer. I mean, I’m a huge wrestling fan, nothing was crazier than wrestling in the 90s. The Attitude Era is crazy, you cannot do any of that sort of stuff nowadays. I think we’re all kind of like looking back 30 years, back and going, “this was a unique time where our aggression was kinda unchecked.”

Chiodi: I think it was the dawn of children’s shows that were done a lot more for money. Like before that, it was Sesame Street and shows like that on PBS. And then you saw the dawn of Barney and Nickelodeon and things that had ads running next to them. And there was this moment where it wasn’t totally regulated. And how you marketed to kids came as like a little bit of an afterthought. And I do think in some ways, we’re in that moment, again, right now, in social media, where everyone is so in this moment of like, “free speech, free speech, free speech,” but like, how do you guide that? Certainly, for underage people? On many levels, dark, dark stuff, like kids seeing pornography down to like bullying in their high school and how that feels magnified from my generation.

Why was everyone but ‘Barney’ creator Sheryl Leach involved in the documentary?

Avallone: For the most part, Sheryl was this person who, even when she was running Barney, avoided any of the bashings, any of the backlash, and avoided any of the negativity. If we called this movie “I Love You,” she should be into it, you know? But the fact that we talked “you hate me,” I think that was the reasoning for her not to be in it. I know Sheryl, I’ve met her because of this project. I had lunch with her before this project even started and we kept in touch by emails. She’s [a] super nice, amazing person. She just doesn’t pay attention to me the negative that happened with Barney

Peacock

Do you think a snarky, irony-fueled Barney remake is possible?

Avallone: I heard one interview with [Daniel Kaaluuya] doing my Barney research, you hear his name get brought up a lot. But like it was like, Okay, well,” I love you, but what happens if you don’t love me? ” You know, and exploring that relationship? I think his is dark. I mean, look, anything’s darker than that show. Right? But it’s just a different approach to Barney, whereas Barney was very much happy, happy, happy. I think this is going to be shades of different emotions if it happens.

What can you tell us about Patrick, Sheryl Leach’s son, as it relates to this doc?

Chiodi: Patrick’s living in his mack daddy house in Malibu with the Barney money, probably a little resentful of the amount of time Barney took away from his own childhood with his mother. And he has a disagreement with his neighbor and goes over there and shoots him. And ends up going to jail for attempted murder. And we chronicle that in that as well.

So you have not only this great story about ”what does this say about our culture now” and the seeds of it. Then you have the story about this amazing teacher, Cheryl. She creates this thing for her son, why does it have all this suspicion? And then you see this piece which is like, how, you know, being rich doesn’t solve all your problems. And there’s like a little “True crime” piece to it, too. So it has many layers to it, which I think is what makes it so fun and entertaining.

Avallone: I feel like everything we say about him is suited because it’s like everything we say around it. You know, like, you can’t just talk about it without knowing everything that went on. It’s very delicate to talk about what happened with the family. You’ll have to watch Episode 2.

I Love You, You Hate Me, Documentary Premiere, Wednesday, October 12, 2022, Peacock