‘Mission: Impossible’ Ended 50 Years Ago: 10 Declassified Facts About the Show

Covert operations, shadowy government agencies, foreign intrigue, technological wizardry, masters of disguises, heist-like action, self-destructing tapes — Mission: Impossible had it all. Oh, and that iconic theme song, of course.

Mission: Impossible ran for seven seasons and 172 episodes on CBS before ending 50 years ago, on March 30, 1973. Steven Hill, Barbara Bain, Greg Morris, and Peter Lupus made up the original Impossible Mission Force — whose missions, should they choose to accept them, involved retrieving sensitive information, recovering ill-gotten goods, neutralizing targets, and averting geopolitical crises.

As the show progressed, the faces of the IMF changed — and not just because of the latex masks the operatives so often wore for disguises. Peter Graves took over as IMF leader, and Martin Landau, Leonard Nimoy, Lesley Ann Warren, and Sam Elliott joined the elite team full-time.

With the Mission: Impossible finale a half century behind us — and the next installment of Tom Cruise’s Mission: Impossible film series only months away — here are 10 facts about the making of the TV show. (Don’t worry — this intel won’t self-destruct anytime soon.)

The 1964 film Topkapi inspired the show.

Topkapi, written by Monja Danischewsky and directed by Jules Dassin, centered on a band of thieves stealing a priceless treasure from a museum. Mission: Impossible creator Bruce Geller took inspiration from the film but shifted the focus to the good guys. (Topkapi also features a wire-dangling stunt similar to that of the 1996 Mission: Impossible film.)

Creator Bruce Geller (literally) lit the fuse on the show.

In the original version of the TV show’s explosive opening credits, it’s Geller’s hand holding a match to the fuse. In the TV revival — more on that below — actor Peter Graves is the one holding the match.

Steven Hill’s Sabbath schedule was one factor in his departure.

Hill, later a star of Law & Order, played IMF leader Dan Briggs in Mission: Impossible’s first season. But as an Orthodox Jew, he had to be home by sundown every Friday to observe the Sabbath and wasn’t available until that Saturday night. This requirement was part of his contract, but it still caused conflict with Mission: Impossible producers, who used him less and less as Season 1 continued and then replaced him with Peter Graves’ Jim Phelps in Season 2.

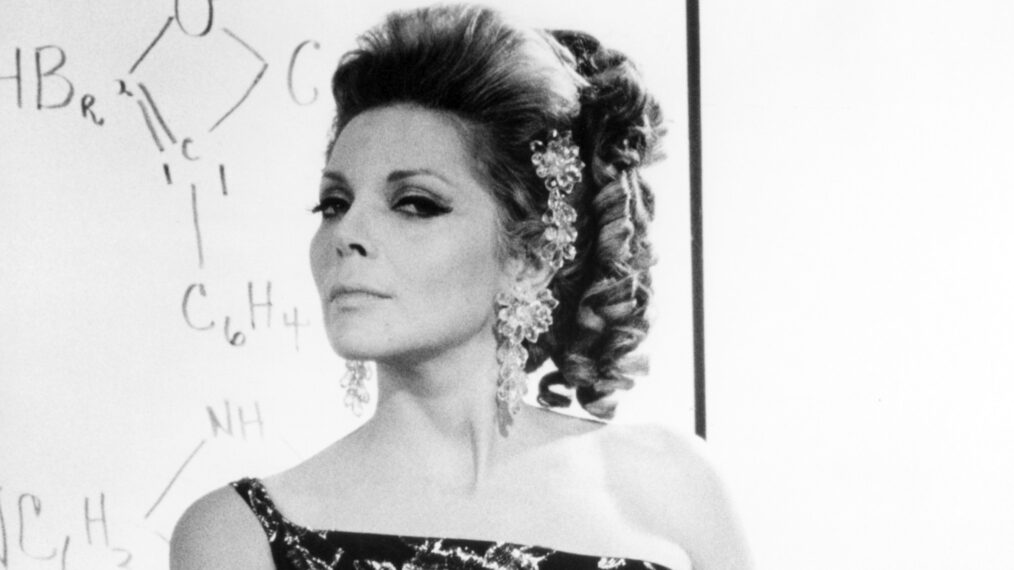

Barbara Bain won three consecutive Emmy Awards for the show.

Bain, who was married to Mission: Impossible costar Martin Landau at the time, won Outstanding Continued Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role in a Dramatic Series — a precursor of the Emmys’ Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series category — in 1967, 1968, and 1969 for playing IMF operative Cinnamon Carter.

Everett Collection

That iconic theme song came together in minutes.

Lalo Schifrin told Emmy magazine in 2016 that he composed the Mission: Impossible theme song under an impossibly tight deadline. “I sat at my desk and wrote that theme in exactly one-and-a-half minutes,” he said. “It was not inspiration; it was a need to do it. It was a little mission — impossible! The whole thing — including the chorus, the bongos, everything you hear — took me maybe three minutes.”

Also, Schifrin wrote the theme song in the rare 5/4 time signature, and the iconic “dun dun, da da” opening spells out “M. I.” in Morse code (as in “dash, dash, dot, dot”).

Mission: Impossible had its own language.

The series employed a fictitious language, nicknamed “Gellerese” by crew members, that was meant “to be easily intelligible to English-speaking audiences but look distinctly German or Polish,” as the Deseret News reported. For example, “machina werke” translates to “machine repair,” “gäz” was “gas,” “emerženc̄iskija” was “emergency,” and “mina din steppen” was the phrase for “mind the step.”

You can thank the show for the verb “self-destruct.”

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, “self-destructive” appeared in the written record in the 1650s, and “self-destruction” appeared even earlier, in the 1580s. But “self-destruct”? “Apparently first attested in the U.S. television series ‘Mission Impossible’ (1966),” the dictionary says.

The 1988 revival initially recycled scripts from the original show.

Amid a writers’ strike in 1988, ABC Entertainment struck a deal with Paramount Television and commissioned a remake of Mission: Impossible — using the original series’ scripts but shuffling up the locales and the cast members, aside from Graves, who reprised his role as Jim Phelps. (A spokesperson for ABC put his best spin on the rehash, saying, “Why tamper with success?”)

Eventually, however, the strike ended, and the ABC version of Mission: Impossible aired new storylines in its two-season run.

1966’s Mission: Impossible and its 1988 revival were a father-son act.

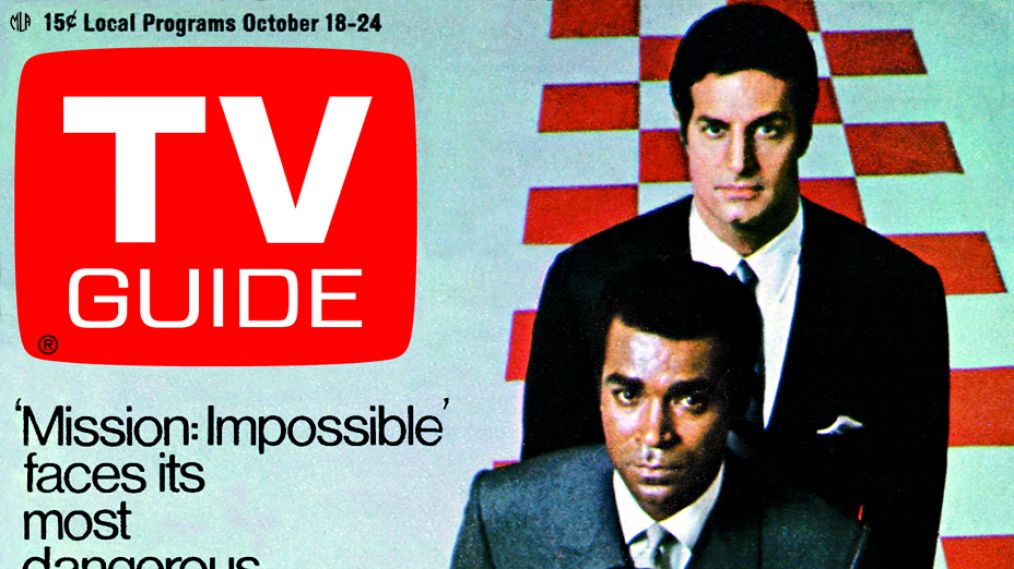

The 1988 revival starred Phil Morris as electronics expert Grant Collier, son of Barney Collier (Greg Morris) from the original series. Phil Morris — who would later go on to recur in Seinfeld, Smallville, and Doom Patrol — is the real-life son of Greg Morris. (See them together in this photo from the 1988 episode “The Condemned.”)

But as Phil told Yahoo TV in 2012, he was originally cast as Barney in the revival, since the writers’ strike meant the producers couldn’t change a word of the script. “When the strike broke, which was right after [everyone] was cast, then they made me, in their infinite wisdom, the son of Barney, which was a role I had been preparing for my whole life,” he added with a laugh.

Jim Phelps returned as a changed character in the first film, much to Peter Graves’ dismay.

1996’s big-screen Mission: Impossible — the start of what has become a $3.5 billion film series — featured Jon Voight taking over the role of IMF boss Jim Phelps. However, the Phelps of the film — spoiler alert! — turns out to be a murderous traitor.

Actor Greg Morris told CNN he walked out of the movie, while Peter Graves mourned what happened to his character. “I am sorry that they chose to call him Phelps,” he said. “They could have solved that very easily by either having me in a scene in the very beginning, or reading a telegram from me saying, ‘Hey, boys, I’m retired, gone to Hawaii. Thank you, goodbye, you take over now,’” the actor, who passed away in 2010, said to CNN. “I felt a little bad that they called him Phelps, and what happens to him happens.”

From TV Guide Magazine

Crime, Comedy & Convenience Stores: Unwrapping Hulu's 'Deli Boys' With the Cast

Cupcakes, corndogs…and cocaine?! Two brothers find themselves in a hilarious pickle when they inherit an unseemly bodega biz in Hulu’s new comedy Deli Boys. Find out how The Sopranos and Real Housewives of Orange County influenced the cast. Read the story now on TV Insider.