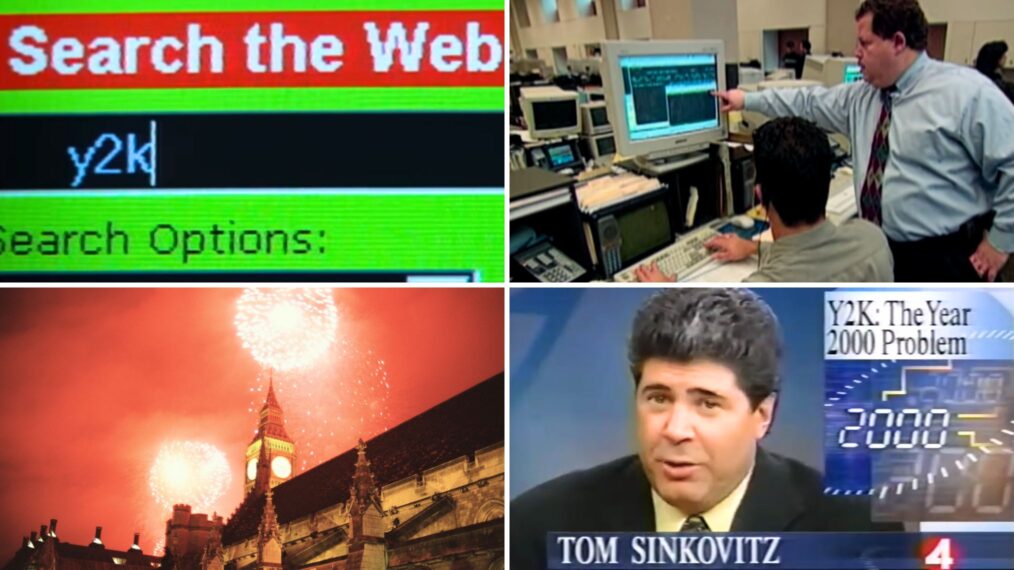

Y2K, 25 Years Later: How TV News Exacerbated the Apocalypse That Never Was

If you’re of millennial age or older (or if you’ve seen a certain comedy-horror film now in theaters), you’re likely already familiar with the “year 2000 problem,” better known by the moniker Y2K. After all, it was practically all the news media could talk about in 1999.

The year 2000 problem was that many early computer programs saved memory by abbreviating years to two digits. And in the days leading up to the new millennium, the concern was that computers would not know to interpret “00” as “2000” and would then fail, causing widespread outages in sectors like banking, communications, utilities, and the government.

Simply put, many feared January 1, 2000, would bring mass chaos.

The news media rabidly covered — and, arguably, contributed to — the panic. “It was a media firestorm,” former New York Times tech columnist David Pogue recalled in a 2023 CBS News New York interview. “Reporters didn’t know if it was real or not.”

Television news contributed to Y2K fears, often running features on survivalists who were unplugging and isolating from society in the run-up to the new year. CNN even offered a Y2K “preparedness checklist” that advised stocking up on food and water as one would in preparation for a natural disaster.

“There was a smorgasbord of Y2K on TV. It was a spectacle ready-made for network news coverage, one of the last hurrahs for a medium that would soon be decimated by computers — which is maybe why the news covered them with such fear,” Dan Piepenbring wrote in an n+1 review of the documentary Time Bomb Y2K.

In that documentary, now streaming on Max, directors Brian Becker and Marley McDonald cover the hysteria around the year 2000 problem. For Becker, realizing he hadn’t heard about Y2K “led to further research and realizing it was on TV essentially every night for two years,” he told Filmmaker Magazine.

As the pivotal Y2K moment drew closer, TV news divisions devoted dozens of hours of airtime to New Year’s Eve. CNN planned 100 consecutive hours of coverage, while MSNBC slated a less-intense 30-hour block, including an early-morning TV broadcast in which Brian Williams and Soledad O’Brien would “let us all know whether the world is still standing,” as The Washington Post’s Lisa de Moraes quipped.

Anxiety turned to relief on January 1, 2000, as doomsday never came. Some glitches were reported, but suffice it to say, reports of the world’s end were greatly exaggerated. Planes didn’t fall out of the sky, nuclear reactors didn’t shut down, and cardiac pacemakers kept ticking.

Instead, TV viewers saw “Sydney lit up, Paris aglow, Berlin bedazzled, and 7,000 television reporters trying to think of something to say amid their 24-hour coverage of nothing,” as The Journal Times’ Rob Golub put it.

Even before the clock struck midnight on January 1, a Chicago Tribune poll found that almost half of those surveyed believed the media had gone too far or exaggerated the coverage of Y2K. “We usually shoot each other looks when it comes up in a newscast,” one woman told the newspaper. “The major discussion my husband and I have has been how this is getting out of hand.”

And after the anticlimactic New Year, Y2K became a punchline for some, while others considered it a hoax. In a letter to the editor of the St. Petersburg Times, one reader chided the media, and TV news in particular, for crying wolf. “An abject apology is due for spreading all the Y2K panic that caused at least some people to expect the worst when, in fact, absolutely nothing happened,” that reader wrote. “Both local and national TV news operations even had some stories that had the theme ‘If you’re not worried about Y2K, you should be.’ This irresponsible garbage was fed to the public night and day for several months.”

Behind the scenes, however, companies had spent millions and programmers had worked for years to make systems Y2K-compliant. “The Y2K crisis didn’t happen precisely because people started preparing for it over a decade in advance. And the general public who was busy stocking up on supplies and stuff just didn’t have a sense that the programmers were on the job,” Paul Saffo, a futurist and adjunct professor at Stanford University, told TIME in 2019.

If you missed the Y2K panic, you get an encore performance in the years ahead. Technology now has a year 2038 problem, and alarmist coverage has already begun.