Stations of the Cross: A.D. and the Resurrection of Epic, Faith-Based TV

It’s the greatest story ever told…and told…and told again. “Hollywood,” says Craig Detweiler, a professor of communication at Pepperdine University, “is constantly forgetting and then remembering this character who is revered and studied by hundreds of millions of people on a weekly basis.” Leave it to Jesus, who went momentarily unrecognized by Mary Magdalene after the Resurrection, to be hiding in plain sight–at least as far as the entertainment industry’s attentions are concerned.

But executives don’t have ADD about the Bible anymore–they’ve got A.D. The Bible Continues, plus a batch of others besides. Even veteran viewers of Good Book-to-boob tube adaptations have never witnessed a wave of biblically based television and movies quite like the tsunami of Scripture TV descending on screens like so much white foam over an Egyptian army. You could see it as an ongoing response to the record-breaking box office of Mel Gibson’s 2004 The Passion of the Christ ($612 million worldwide) or just a cyclical reiteration of how every third generation needs its own King of Kings or Ben-Hur. Maybe it’s even a sign that spirituality is blossoming in Hollywood’s executive boardrooms. (Insert holy laughter here.) But heathens and believers suddenly have more 2,000-year-old entertainment choices than you can shake a study Bible at.

Most have been one-offs, but NBC’s A.D. has the legs and plotlines to last well past Ascension Day. Attracting 9.5 million viewers in its Easter debut and handily winning the night, the series is scheduled for a 12-week run–and producers Mark Burnett and Roma Downey hope it will score a second season. (If you saw the first-episode spoiler that had Jesus telling Peter, “One day you will die for me,” rest assured the show’s creators will be putting off the fulfillment of that Easter egg for as long as possible.) Religio-historical dramas aren’t just for basic cable anymore, not after Burnett and Downey’s The Bible premiered to 13.1 million viewers on the History channel in 2013.

For evangelicals, A.D. is the draw of the season, although other religious constituencies have also been addressed. The slightly skeptical had the National Geographic Channel’s Killing Jesus. For the somewhat more skeptical: CNN’s alliterative documentary Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery. Then there was CBS’s The Dovekeepers, Downey and Burnett’s fictionalized drama set at the first-century fortress of Masada, in which its comely leads got to know one another in the biblical sense.

A similar boom is evident in cinemas, with Burnett and Downey having successfully re-edited The Bible into the 138-minute 2014 feature Son of God. “The fact that Christians went to theaters and watched a repackaged version just because they wanted to make a statement is a sign of how desperate they are to see their values affirmed,” says Mark Joseph, a Christian producer and marketing consultant, about Son of God‘s $68 million worldwide gross. Last year also saw a pair of fanciful Old Testament movies in Noah and Exodus: Gods and Kings, although their disappointing returns may be indicative of what happens when auteurs tick off the faithful. It remains to be seen whether churchgoers will feel wooed or shooed by an adaptation of Anne Rice’s controversial Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt that’s in postproduction or by the movie about the New Testament’s most celebrated convert, Paul, that’s just been announced with Hugh Jackman, Ben Affleck, and Matt Damon producing. Meanwhile, the redoubtable Burnett and Downey are behind a big-screen Ben-Hur remake that’s currently in production. Looking for a smart investment in 2015? You might want to consider the toga and tunic industries.

A.D. focuses on the apostles’ ministries after Christ’s resurrection and ascension–although you may notice a lot more foot chases, villainy, and bloodletting than the author of the Book of Acts ever transcribed. If the series does get extra-biblical, however, conservative Christians trust Burnett and Downey as two of their own. Last year, in promoting Exodus: Gods and Kings, star Christian Bale described his Moses as “likely schizophrenic.” No worries about any such heresy with this duo at the helm.

Phil Cooke, an evangelical writer and producer of the upcoming Christian-music movie Hillsong: Let Hope Rise, defends the traditionalist approach. “There’s no question that Hollywood is getting the message that the more biblically accurate the movie or TV series, the greater the audience,” he says. “Mark and Roma are proving that. The great challenge is that movie studios and TV networks aren’t Christian organizations. They’re driven by creative people who want to put their own spin on stories.” As a creative professional himself, Cooke understands that impulse, adding, “If I were shooting a classic fairy tale, I would want to bring something new to telling that story. And since many of these filmmakers aren’t believers, they look at these Bible stories the same way I’d look at a fairy tale.”

Author and radio host Eric Metaxas, a celebrated figure in evangelicalism since writing a best-selling biography of German Christian hero Dietrich Bonhoeffer, concurs. “Mark and Roma bring a much-longed-for respect to biblical narratives, one that’s been sorely lacking in recent decades,” he says, adding that exhibiting perceived contempt for your core audience will never fly. “[Martin] Scorsese’s unintentionally hilarious The Last Temptation of Christ, with Willem Dafoe as a mealy-mouthed pseudo-savior, was the first of these fiascoes. A.D. is proving the magnitude of the audience interested in a serious treatment of biblical subjects.” His enthusiasm has been echoed in positive notices from the presidents of the National Religious Broadcasters, Focus on the Family, and the Southern Baptist Convention, among others.

Although Killing Jesus didn’t get nearly the same endorsements, the three-hour drama made a killing (sorry) for National Geographic; with 3.7 million viewers, the premiere boasted the network’s largest audience to date. The big bow came in spite of brickbats from such conservative Christian outlets as Movieguide.com, which warned that the TV movie offered “a Jesus who’s not divine, who performs no miracles, and who’s full of doubt,” before concluding, “We suggest viewers skip watching Killing Jesus and watch A.D. instead.”

[jwplatform MZlcapou]

One person who’s been involved in marketing religious projects to Christians (and prefers not to be identified because nearly everyone in evangelical media circles ends up working together at some point) posits that Bill O’Reilly, an executive producer and coauthor of the source book, “essentially did a secular version of Jesus’s story, and the only reason it didn’t get organized protests is because he’s on Fox News. A lot of Christian viewers like his political views but can’t figure out his faith.”

Getting pegged as the open-minded person’s guide to Christ was fine by Nat Geo, which wanted to play Killing Jesus as religiously nonpartisan. “This is a story that has been told trillions of times,” says Heather Moran, the network’s executive vice president of programming and strategy. “By stripping away what was most familiar to so many, it [became] such a powerful story. That was a very conscious choice of ours, to keep those details open to interpretation so different viewers with different perspectives could come to this historical spine of a story and use it as a jumping-off point for what they personally might bring to the table.” In the end, Killing Jesus split the difference between faith-based and secular audiences–leaving any resurrection off screen but still showing an empty tomb–and for all the publicized emphasis on outside history and scholarship, it took many of its events and dialogue straight from the gospels.

A.D. gave us a majestically backlit warrior-angel rolling away the stone, while the dustier Killing Jesus preferred to let the mystery be. What the two have in common is how they essentially play out as political thrillers, not spiritual reveries. In the days of such Cecil B. DeMille biblical epics as 1949’s Samson and Delilah, the joke (and maybe reality) was that churchgoers ostensibly came for the piety but stuck around for the chance to see sinful temptresses in skimpy outfits. The modern analogy is in how much these new projects make the religious aspects somewhat secondary to the machinations of the bad guys. None has gone quite as far as the musical Jesus Christ Superstar, which had the temerity to bump Judas up to colead. But Pontius Pilate is almost always going to wind up being a more fun character to depict than a Messiah whose most famous cryptic aphorisms aren’t about to get a dialogue polish.

If you’re a Christian tired of seeing the Messiah alternately portrayed as a stiff, saintly victim or (occasionally) tortured neurotic, you might consider the historical taboo on filmic portrayals of Muhammad and develop a slight case of Muslim envy. Back in the CinemaScope era, Christ arguably made a greater impression as a cameo player in Ben-Hur, showing up just long enough to have the hem of his garment touched, than he did in the whole of The Greatest Story Ever Told. So part of the canniness of A.D.–not to get too irreverent about it–is that the series kills off this dramatically risky and unwieldy character before the first commercial break and doesn’t even let Jesus stick around past the second hour, so as not to get in the way of all the bloodshed, Lady Macbeth-style conniving, and disciples-on-the-run action that make it more of a diverting potboiler than a Sunday-school lesson.

The Old Testament doesn’t present as great a risk in adaptation as do Jesus’s red-letter words. But filmmakers can still run into danger–as demonstrated by Exodus: Gods and Kings director (and Killing Jesus executive producer) Ridley Scott’s divisive decision to portray God as a petulant boy and Darren Aronofsky’s infamous rock monsters in Noah. “In order for a biblical epic to be financially successful, you need the evangelical audience to become engaged,” says Matthew Paul Turner, author of Our Great Big American God and a leading figure in the progressive Christian movement. “But evangelicals are nitpicky about the details of their Bible stories, often carrying the persona of ‘protectors’ of God’s stories. That’s why Noah infuriated many of them, because rather than being able to sit back and enjoy a creative expression loosely based on Genesis, they squirmed at every turn away from how the Bible portrays the Great Flood.” There is a mainline church audience that isn’t hung up on absolute biblical literalism, says Turner, who believes “progressive Christians mostly just want to see a well-told story, one that doesn’t overplay the torture of Jesus for dramatic effect and one in which Jesus isn’t a hot white guy.”

The emphasis on bloodshed in most of these adaptations doesn’t sit well with some mainline Christians–not even when it’s Jesus’s blood. “In journalism, the standard is ‘If it bleeds, it leads,’ and I think it’s the same in these sensationalist film depictions of Christ,” says Rev. Kathy Cooper-Ledesma, pastor of Hollywood United Methodist Church, which has many constituents from the entertainment industry. “They’re all about the substitutionary-atonement theory, focusing on violence and guilt and the belief that God required a blood sacrifice. That’s not the God I believe in at all. The greater story we celebrate is the love of God, but these TV shows don’t consider that dramatic enough.”

And then there are believers who just think other TV shows are better at illustrating the Bible than, say, The Bible. “I’m far more intrigued by the spiritual, ethical, and moral questions raised by Orphan Black or Sons of Anarchy,” says Cathleen Falsani, author of The Dude Abides: The Gospel According to the Coen Brothers, “than I am interested in another film interpretation of a biblical story that may or may not have a hidden religious or political agenda.”

A.D., as it goes along, will inevitably delve more into the realm of pure speculation, as accounts of the disciples’ post-Pentecost lives get harder to divine from the sketchy scriptural narratives. And based on the good will that Burnett and Downey have already built up in conservative Christian circles, they’ll probably get away with making up more of the details. But in one early scene in A.D., before Jesus leaves the building, you get a glimpse of what could have been in a straightforward Christ-tale telling. Jesus, popping up at his followers’ hideout, at first spooks them with his ability to forgo niceties such as entering through doors. And then, with a big grin, he asks, “Is there any food?” That’s a Jesus we could still stand to see more of on screen, even after all these tellings: one who is as in touch with his human side–and not even in a tortured way–as his followers are hungry for divine revelations.

A.D., Sundays, 9/8c, NBC

From TV Guide Magazine

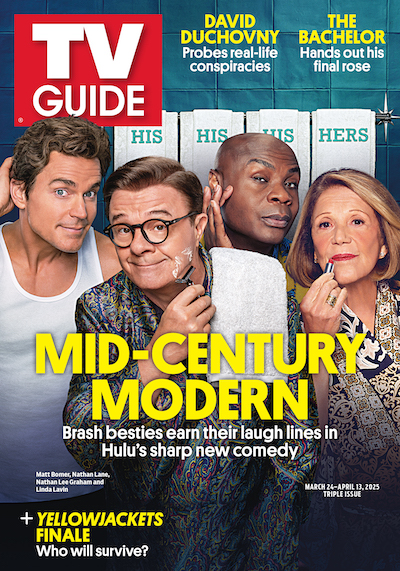

How Hulu's 'Mid-Century Modern' Is a 'Golden Girls' for Our Times

Settle in for some older and bolder laughs with the BFFs of a certain age in the new comedy starring Nathan Lane, Matt Bomer, and Nathan Lee Graham. Read the story now on TV Insider.