‘Sharknado 3’ and the Cycle of Intentional Garbage

“Nobody ever sets out to make a sh-tty movie,” a writer of sh-tty TV movies once told me.

This is not exactly true, though I don’t think he was intentionally lying to me so much as lying to himself (especially since he’d just described the pitch process at a certain network as throwing out a bunch of ridiculous names and seeing which ones the executives liked best).

The thing is, we do live in an age in which people set out to make sh-tty movies, mostly for television or straight-to-video, in an effort to capitalize on the current cultural yen for garbage. This is a bad thing. TV executives aren’t entirely at fault here—their job is to make things that people will watch. And people will watch, even if it’s just to participate in some kind of performative digital effigy-burning. As cynical viewers want to look cool by ironically loving something bad, TV makers create intentional artistic trainwrecks to target viewers who want to look cool by ironically loving something bad—cynicism squared.

It’s one thing to embrace the insanity and awfulness of something like The Room, which was made with genuine intent. But hearing people talk about how “awesomely bad” Sharknado 3 is going to be, and how much they’re going to love it, is vaguely repulsive: If you know it’s going to be bad, you also know it’s being marketed as being bad. You are creating a Cycle of Intentional Garbage. It’s the difference between laughing when your friend accidentally steps on a rake and laughing when your friend hits himself in the head with a rake specifically to get you to laugh at him, because, hey, you did when it was just an accident.

The B-movies of the 1960s started to lay the groundwork for this cycle, followed by snarkfest programming like Mystery Science Theater 3000. Yet Gen Y (to which I belong) has taken the concept a step further by adding yet another layer of self-awareness. There are multitudes out there for whom the opportunity to make a dumb joke about a terrible TV movie inspires an excitement akin to bloodthirst. Are we embracing this Cycle of Intentional Garbage because we created it, so we couldn’t be hurt by the mountains of Unintentional Garbage that seem to ring us in?

You might think we have reached the apex of Trash Mountain with Sharknado 3. It was a marketer’s dream, with all the “brand integration” and “product placement” for various NBC Universal properties and select sponsors. There were approximately 543 “celebrity” cameos, a special trip to show just how great Universal Studios Orlando is when the sharks aren’t around, zero attempts at coherent plotting, and a budget of perhaps $5.57—all to capitalize on your need to crack wise about Tara Reid’s robot arm. But this was not the summit. On the contrary: Sharknado 3 is one step down from the top.

We reached Peak Intentional Garbage back in June, with the much-ballyhooed Will Ferrell and Kristen Wiig Lifetime movie A Deadly Adoption. Plenty of irritating nostalgia-twisters had come before this one: the unofficial Saved by the Bell biopic, whatever the hell the Lindsay Lohan-Liz Taylor thing was. And plenty will come after: the similarly “unofficial” Full House and 90210 and Melrose Place movies are already in the works. Adoption, though, used two beloved comedic forces to ratchet up the buzz, applying a sheen of intrigue after the project was at one point declared “dead” by Ferrell and Wiig, only to be “resurrected” a few weeks before it aired.

The internet, of course, went bazoo for all of these things. The problem with this particular movie, however, was that while Ferrell and Wiig may “genuinely” love Lifetime movies, the audience was still operating under the assumption that it was a joke, despite no evidence to support such an assumption. There’s a fine line between parody and parity— a line that disappeared in this case. When viewers can’t even tell the difference between Intentional and Unintentional Garbage, the ensuing confusion takes on a sickly vibe, millions of tweets be damned, and the Cycle becomes a Vortex.

Yes, people who get precious about Their Art are the worst, but wanting things to be good is not wrong. Cringing at the calculated nastiness of something like the Saved by the Bell Lifetime movie or Sharknado 8 Them All doesn’t make you a killjoy. It makes you the kind of person who doesn’t want to live in a world where contempt for art and consumers is rewarded, where authenticity and genuineness are shut out. It makes you an anti-cynic, and that is a good thing.

From TV Guide Magazine

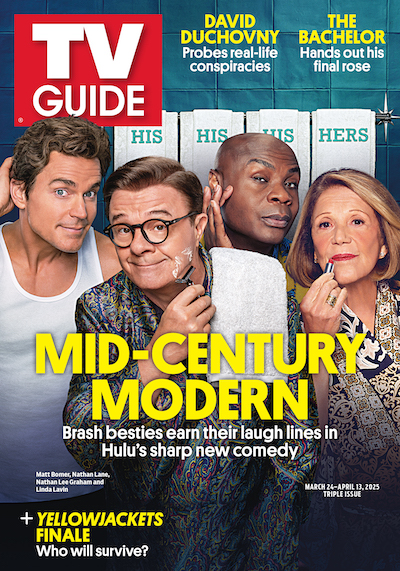

How Hulu's 'Mid-Century Modern' Is a 'Golden Girls' for Our Times

Settle in for some older and bolder laughs with the BFFs of a certain age in the new comedy starring Nathan Lane, Matt Bomer, and Nathan Lee Graham. Read the story now on TV Insider.