‘The Long Road Home’: Jeremy Sisto Says His Character ‘Is Like No One I’ve Ever Met’

To play The Long Road Home‘s deeply conflicted Staff Sergeant Robert Miltenberger, Jeremy Sisto had to mine emotional territory the actor couldn’t possible know first-hand.

In April 2004, Miltenberger was a world-weary career soldier whose imminent and longed-for retirement was kiboshed when he was stop-lossed for a humanitarian mission to Baghdad. The 1st Cavalry Division brigade was newly arrived at Camp War Eagle outside of Sadr City when a simple Honeywagon assignment turned into an ambush now known as Black Sunday. The attack and resulting rescue effort landed Miltenberger and his untested young soldiers in the midst of a living hell that would ultimately leave eight men dead, some 50 others injured and the Iraq conflict redefined.

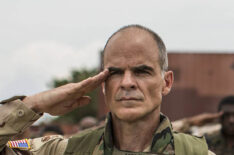

Jeremy Sisto portrays Staff Sgt. Robert Miltenberger on set of The Long Road Home at Fort Hood, Killeen, Texas.

Months later, a traumatized Miltenberger stood on a Sadr City street with his flak vest open, daring the insurgents responsible for the devastation to take him out, too. Diagnosed with PTSD, a conclusion he refutes, Miltenberger retired from the Army in 2005, earning a silver star for his Black Sunday efforts. It brought little comfort. The notoriously introspective Miltenberger told then ABC News chief White House Correspondent Martha Raddatz, “I feel guilty because I wasn’t shot too. I didn’t get hurt. I feel guilty that they awarded me and didn’t award everybody else.”

And his woes didn’t end stateside. Five months after he retired, Miltenberger, his wife Belinda and their two kids lost everything to Hurricane Rita. The quiet Southerner soldiered on, suffering in private and keeping Belinda in the dark about his Black Sunday experiences until she learned of a Nightline episode about the battle and ordered a VHS copy.

In 2007, Raddatz would publish The Long Road Home, her account of the events of Black Sunday as seen through the eyes of the soldiers and their terrified families back home at Fort Hood. Now the subject of National Geographic’s impressive, impactful event series of the same name, The Long Road Home would eventually inspire a group of soldiers and their families to form an unbreakable brotherhood that all say is healing in ways therapy and supports groups cannot match.

TV Insider talked with Sisto about the honor and impact of playing Miltenberger.

Tell me a bit about the process of stepping into this guy’s skin and realizing what a complicated character he was and what a complicated thing you were about to do.

Jeremy Sisto: We’re staring into the heart of this real-life experience that’s so on a different level as far as difficulty, as far as pure human challenge. If you haven’t gone through it, which I obviously haven’t, it is very difficult to walk away feeling like: “Yeah, I stepped into that skin.” You can’t work hard enough to walk away from an experience like that feeling anything but “God, I hope we did it justice.”

The best you can hope for as an actor is that you understand the story that you’re telling, and that you work hard to express that to the audience, so that when it’s all put together in the end, hopefully it takes some of the burden away from the soldiers having to live with these experiences alone. And it gives viewers a real insight, a real intimate look into what it means—not just as a soldier, but as a spouse, as a child, as a community—to go through a war. I hope that General Volesky and Belinda and Robert, if they watch it, feel that it was represented in a way that, at least to some degree, lessens their load.

What was it like for you to know that soldiers who were actually part of the ambush and rescue were on set as you filmed?

You’re in a level of hell and a level of chaos that is unfathomable to somebody who hasn’t been inside it. So, I always felt up against something—a huge abyss of an experience that I’ve never understood. But some of them have said that they felt like a burden was lifted to have these experiences and the men that lost their lives unveiled in a way that is so public. That it felt very relieving to them. And so, I got to take that gratitude that they’re showing and really hold it dear to my heart.”

They’ve been very vocal with reporters about how much they appreciate the actors’ dedication.

There was a real bonding thing amongst the soldiers and the actors, because there is a similarity there. Soldiers, oftentimes when they come out of those situations, they do want to be understood. They had a desire similar to actors who have this desire to go after something that feels bigger than them and to go deeper inside of their own trauma and unveil that stuff. To challenge themselves in big ways. There’s a kinship there, just to have people there that weren’t therapists, but their job was to be empathetic to them. They kept saying: “You guys make us feel like rock stars.” We were all enamored with them. I don’t get star struck by many, but I was definitely enamored by them.

Jeremy Sisto portrays Staff Sgt. Robert Miltenberger on set of The Long Road Home at U.S. Military post, Fort Hood, Killeen, Texas.

In the heat of battle, Miltenberger tells one of his wounded men an untruth that is necessary in the moment, but has a devastating impact on Miltenberger moving forward. I watched you film that scene and you were clearly affected by what you portrayed.

It was just something you say in the moment—but, for Robert, that carried a lot of guilt, a lot of emotion. But I think if it wasn’t that moment, it would have been another moment that he focused it on. Because there’s no way to walk away from that situation, that kind of hell, that kind of trauma, without having a bad feeling. Without having a stark, sad, shitty feeling that manifests itself as guilt. Because you feel shitty about yourself just being in it and surviving.

So it was hard to play, because you don’t want to overplay that moment. We talked about it a lot. We want to honor the fact that that’s what he focuses on, but what’s more important—and hopefully he’ll watch that and be like, “Oh, maybe that wasn’t that bad of a thing to say”—is to represent how horrific this situation is to be in. How any human being going through this situation is going to come out of it with bad feelings about themselves and about the world, and to try to create that experience for an audience that hopefully has some positive benefit on understanding on the soldiers and that world.

This was a guy who was just fine not being a military rock star, fine providing for his family, getting in, getting out—and then he is sent back. He’s already scarred—and then he has a premonition about what is going to happen. What did you tell yourself about that part of Miltenberger and his story?

For me, at least in the beginning of the story, there’s almost a sense of a dream-like quality. Where, having a premonition like that, in some way removed him. Obviously, this is a dramatized telling of the story, but what I was going for was this feeling that he was slightly removed from his own existence. That he was at a distance from his own emotions, from his own experience, that he had disconnected from himself.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wWfeGFAx5w

So, there’s a real sense in the first couple episodes before this stuff happens, that he’s not in a great place to be a soldier. He’s got one foot out the door and that’s what his underlings, his troops, see in him. But then, as the story goes on, you see another side of him. And the other side is someone who loves these kids a lot, and just knows what the effect war can have on these kids. And he hates it. And yet he also loves it. In real life, he would always go back. Says that it’s great, that there’s a camaraderie that you have that.

There’s a real contradiction within him. He’s like no one I’ve ever met.

The Long Road Home, Tuesdays, 10/9c, National Geographic