‘Star Trek’s Walter Koenig On Chekov’s Haircut and Other Decades-Old Rumors

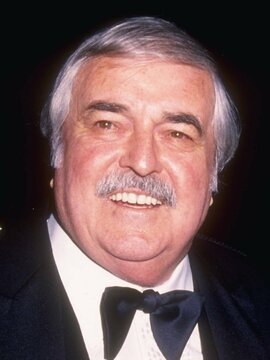

Walter Koenig today

He was as upwardly mobile as the Enterprise itself. Walter Koenig joined Star Trek in 1967 as Pavel Andreievich Chekov, an eager young ensign who would occasionally replace Mr. Spock at the science officer station. By the first Trek movie, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Chekov was tactical officer and chief of security, and even rose to the rank of commander in chief of Starfleet in a later Trek novel written by William Shatner.

But while the character’s ascent is well documented, his arrival during Trek’s second season is shrouded in legend and more than a few goofy rumors. Was Chekov really added to the show because the U.S.S.R. had complained there were no Soviets in Starfleet? Was Koenig so poorly treated on the set that he was forced to share a script with George Takei? And what’s the real deal with Chekov’s mop-top hairdo? We sat down for a chat with the delightful 79-year-old Koenig to get the facts.

RELATED: Star Trek Convention Beams Into NYC With The Voyage Home Staged Reading, Cast Reunions and Shatner

It’s been said that Gene Roddenberry was trying to appease the Russians by creating Chekov. Or was that just the work of an overactive studio publicist?

I don’t know how that Soviet Union story got started, but it’s not true. Chekov was all about demographics. They wanted a male character who could bring in the 8- to 12-year-olds. Gene once showed me a memo that he’d sent to his staff that said, “Let’s look for somebody who has the same appeal as that young Davy Jones fellow on The Monkees.” The reason Gene made Chekov a Russian was because he recognized that the Russians had beaten the Americans into space and he felt that their achievement should be honored. That was Gene.

This came at a time when the Cold War between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. was raging. Did you ever get flak for playing a Russian?

Never. Gene’s plan worked. Pretty soon I was getting the third highest amount of fan mail on the show, after Shatner and Nimoy, and I was really clicking with the kids. They weren’t interested in Chekov’s nationality. [Laughs] They just liked his groovy haircut!

Which caused you a few problems, according to the lore.

They put me in a lady’s wig for my first six or seven episodes, until I could grow my own hair out. But then my hair was already starting to thin, so they had to spray it and comb it forward. It took a little work to make me appealing to the preteen crowd.

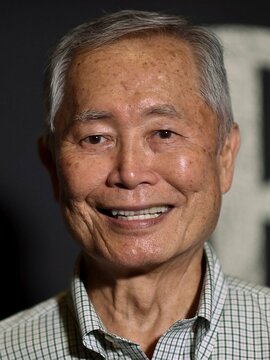

What about the story that you and Takei not only had to share a dressing room but a script as well?

A script? Never. But I do recall we had to share a dressing room for a few episodes, and Jimmy Doohan was also in there with us. Eventually, they managed to find all three of us a room of our own. They weren’t being demeaning. We were supporting players and there was a caste system back then. We didn’t think twice about it. We weren’t stars.

RELATED: CBS’ Star Trek Reboot Recruits Gene Roddenberry’s Son and Trevor Roth

What do you remember about your audition?

It was bizarre. The scene they gave me to read required a lot of tension and stress because the ship was in jeopardy, so I did it with all the appropriate seriousness. And then they said, “Uh, could you do it again, only this time make it funny?” So I did. Then I waited around for two-and-a-half hours. As it turned out, they’d picked me for the part but nobody had let me know. Everybody thought someone else had told me. So I’m sitting there wondering what the heck’s going on, and all of a sudden a man shows up and takes me to the wardrobe department. He drops to his knees and puts his hand on my crotch. I said, “Hey, what are you doing?” He said, “Well, I have to measure you for a costume, don’t I?” [Laughs] That’s how I found out I was going to be on Star Trek!

You were not part of the first season, when hope for the show was really alive. What was it like to show up when it was in trouble?

There was a lot of friction between Gene and NBC, because they kept trying to repress what we were doing. The network wanted to either get rid of us or change us. They wanted Star Trek to be more banal so we’d have a greater fanbase, one that went beyond the sci-fi and fantasy audience. They wanted us to appeal to everybody, so they kept trying to castrate the project. But Gene was stubborn.

Was all that stress hard on you actors?

Not really, mostly because we only learned how truly bad things were kind of after the fact. We just stayed focused on our performances. It’s hard to get too stressed out when your job requires you to wear pajamas.

Did you really know what you were doing at that navigation console?

Not a clue. We were surrounded by all this machinery and equipment I didn’t remotely understand. So I’d push the blue button when I was feeling depressed, and the green button when I was feeling envy. [Laughs] It was very arbitrary.

Was making the first Trek film as difficult as we’ve heard?

And more. The first day on the set was really amazing. We began with a scene of the lift door opening and Captain Kirk stepping out, and Uhura and Sulu and Chekov come rushing up to him. After all the disappointment of having our series canceled and some false starts on the movie, it was so thrilling to finally be there. I was, like, “My God, we’ve really done it! This is incredible!” But soon the problems were evident. We didn’t have a third act in the script. They had only written two acts and nobody knew how the story would end. We’d show up for work and they’d tell us to go eat bagels and have coffee, and that would go on for hours and hours because Gene and the writer, Harold Livingston, and the director, Robert Wise, were in conference trying to figure out an ending. Then, to complicate matters, Leonard and Bill had it in their contracts that they too had input in the script. So we had a lot of cooks. It was madness.

RELATED: Leonard Nimoy’s Son Adam on Making For the Love of Spock a Reality

But it’s all been worth it?

I’ve had a ball. I went into Star Trek thinking I was just a day player and that maybe, if I was really lucky, I might get to recur. So to be here talking about it on the 50th anniversary is just remarkable. Sure, I complained here and there about Chekov not being given enough to do, but now my posture is this: If I’m going to be known at all after I’ve departed this mortal coil, it will be as Chekov, and only as this character, and I’m happy with that. I was here for something truly wonderful that has garnered due respect and had something really significant to say about the way we human beings should be operating in this world. I am so very proud of that.