Dick Clark

Credits

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2012

Host

Show

2011

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2012

Host

Show

2011

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2011

Host

Show

2010

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2011

Host

Show

2010

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2010

Executive Producer

Show

2009

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2010

Host

Show

2009

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2010

Executive Producer

Show

2009

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest 2010

Host

Show

2009

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest

Host

Show

2008

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve With Ryan Seacrest

Host

Show

2008

2008 Golden Globes Red Carpet Special

Executive Producer

Show

2008

The Wrecking CrewStream

Self

Movie

2008

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve 2008

Host

Show

2007

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve 2008

Host

Show

2007

The $100,000 Pyramid

Host

Show

2007

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve 2007

Host

Show

2006

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve 2007

Host

Show

2005

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve 2006

Host

Show

2005

The 40th Annual Academy of Country Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2005

2005 Golden Globe Arrivals Special

Host

Show

2005

Golden Globe Awards -- 62nd Annual

Executive Producer

Show

2005

Golden Globes Arrival Special

Executive Producer

Show

2005

The 62nd Annual Golden Globe Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2005

Celebrity A-List Bloopers

Host

Show

2005

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve 2005

Executive Producer

Show

2004

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve 2005

Executive Producer

Show

2004

TV Guide: Greatest Moments 2004

Executive Producer

Show

2004

The 32nd Annual American Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2004

The 39th Annual Academy of Country Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2004

ABC Extreme Bloopers

Host

Show

2004

The 31st Annual Daytime Emmy Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2004

Golden Globes Arrival Special

Executive Producer

Show

2004

The 61st Annual Golden Globe Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2004

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve 2004

Executive Producer

Show

2003

Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve 2004

Host

Show

2003

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve 2004

Executive Producer

Show

2003

Dick Clark's Primetime New Year's Rockin' Eve 2004

Host

Show

2003

TV Guide: Greatest Moments 2003

Executive Producer

Show

2003

American Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2003

The AMA Red Carpet Party

Executive Producer

Show

2003

ABC Bloopers

Host

Show

2003

Sam Cooke: Legend

Self

Show

2003

The 38th Annual Academy of Country Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2003

All ABC Bloopers

Executive Producer

Show

2003

All ABC Bloopers

Host

Show

2003

ABC's 50th Anniversary Blooper Celebration

Host

Show

2003

American Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2003

American Dreams

Executive Producer

Series

2002

More Classic TV Bloopers

Executive Producer

Show

2002

More Classic TV Bloopers

Host

Show

2002

Confessions of a Dangerous MindStream

Self

Movie

2002

Bowling for ColumbineStream

Actor

Himself

Movie

2002

Bowling for ColumbineStream

Self

Movie

2002

The Other Half

Host

Show

2001

The 3rd Annual Family Television Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2001

The 36th Annual Academy of Country Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

2001

Spy KidsStream

Actor

Financier

Movie

2001

Winning Lines

Host

Show

2000

More Bloopers

Executive Producer

Show

1999

More Bloopers

Host

Show

1999

Bloopers

Executive Producer

Show

1999

Bloopers

Host

Show

1999

FuturamaStream

Guest Voice

Himself

Series

1999

Hollywood Rocks and Rolls in the 50s

Music Performer

Show

1999

Hollywood Rocks and Rolls in the 50s

Self

Movie

1999

Neighbors From Hell

Executive Producer

Show

1998

25th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards

Executive Producer

Show

1998

An All-Star Party for Aaron Spelling

Executive Producer

Show

1998

Will You Marry Me?

Executive Producer

Show

1998

TV Censored Bloopers '98

Executive Producer

Show

1998

TV Censored Bloopers '98

Host

Show

1998

Meet Hanson

Executive Producer

Show

1997

Jenny

Guest Star

Show

1997

Dharma & Greg

Guest Star

Series

1997

The Weird Al ShowStream

Executive Producer

Series

1997

The Weird Al ShowStream

Guest Star

Series

1997

The $25,000 Pyramid

Host

Game Show

1997

Beyond Belief: Fact or FictionStream

Executive Producer

Series

1997

The 32nd Annual Academy of Country Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

1997

Just Shoot MeStream

Guest Star

Himself

Series

1997

Deep Family Secrets

Executive Producer

Movie

1997

Sabrina the Teenage WitchStream

Guest Star

Series

1996

Annual Primetime Emmy Awards

Executive Producer

Show

1996

Arli$$Stream

Guest Star

Series

1996

The 31st Annual Academy of Country Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

1996

The Good Doctor: The Paul Fleiss Story

Executive Producer

Movie

1996

The Drew Carey ShowStream

Guest Star

Series

1995

The 22nd Annual Daytime Emmy Awards

Executive Producer

Show

1995

FriendsStream

Guest Star

Himself

Series

1994

Secret Sins of the Father

Executive Producer

Movie

1994

The X-FilesStream

Guest Star

Dick Clark

Series

1993

The American Music Awards

Executive Producer

Show

1993

Elvis and the Colonel: The Untold Story

Executive Producer

Movie

1993

Mad About YouStream

Guest Star

Himself

Series

1992

Hangin' with Mr. CooperStream

Guest Star

Series

1992

The 12th Annual ACE Awards

Actor

Show

1991

Death Dreams

Executive Producer

Movie

1991

The Fresh Prince of Bel-AirStream

Guest Star

Series

1990

The SimpsonsStream

Guest Voice

Himself

Series

1989

Murphy Brown

Guest Star

Series

1988

The ABC Fall Preview Special

Actor

Show

1986

Tenth Annual Circus of the Stars

Actor

Show

1985

Copacabana

Executive Producer

Movie

1985

Remo Williams: The Adventure Begins

Executive Producer

Movie

1985

The Demon Murder Case

Executive Producer

Movie

1983

Police Squad!

Guest Star

Series

1982

The 32nd Annual Primetime Emmy Awards

Host

Show

1980

Valentine Magic on Love Island

Executive Producer

Movie

1980

The Dark

Producer

Movie

1979

Birth of the Beatles

Executive Producer

Movie

1979

The Man in the Santa Claus Suit

Executive Producer

Movie

1979

Deadman's Curve

Self

Movie

1978

Telethon

Actor

Irv Berman

Movie

1977

TattletalesStream

Guest

Game Show

1974

The Partridge FamilyStream

Guest Star

Himself

Series

1970

The Odd CoupleStream

Guest Star

Himself

Series

1970

Adam-12Stream

Guest Star

Series

1968

It's Happening

Producer

Show

1968

The Dick Cavett ShowStream

Guest

Talk

1968

Happening '68

Actor

Show

1968

Wild in the Streets

Actor

TV Newscaster

Movie

1968

Killers ThreeStream

Actor

Roger

Movie

1968

Killers ThreeStream

Producer

Movie

1968

The Savage Seven

Producer

Movie

1968

The Woody Woodbury Show

Self

Show

1967

Branded-1965

Guest Star

Series

1965

Dick Clark Dr. Pepper Show

Host

Show

1963

The Object Is

Host

Show

1963

Ben Casey

Guest Star

Dr. David Langley

Series

1961

The Young Doctors

Actor

Dr. Alexander

Movie

1961

Because They're Young

Actor

Neil Hendry

Movie

1960

Dick Clark's World of Talent

Host

Show

1959

The Dick Clark Show

Host

Show

1958

Perry MasonStream

Guest Star

Leif Early

Series

1957

JamboreeStream

Self

Movie

1957

Lassie

Guest Star

J.H. Alpert

Series

1954

American Bandstand

Host

Variety Show

1952

What's My Line?Stream

Guest

Game Show

1950

News aboutDick Clark

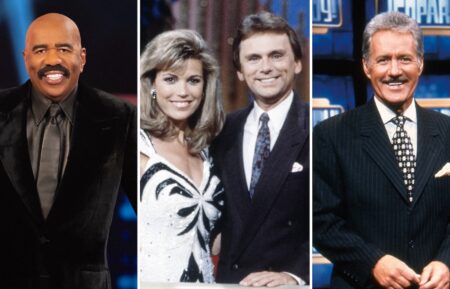

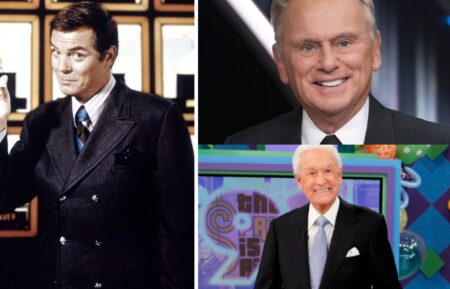

Love Pat Sajak? Don’t Forget These 17 Other Game Show Hosts (PHOTOS)

Is Pat Sajak the Greatest Game Show Host of All Time? (POLL)

9 Unforgettable Moments From ‘Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve’

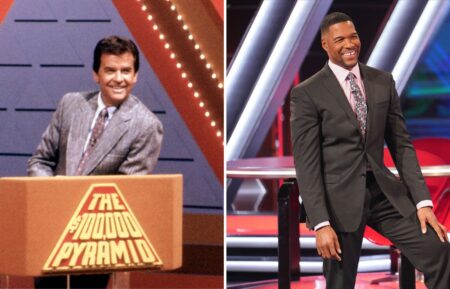

‘Pyramid’ Turns 50: See Every Host Who Has Emceed the Game Show

Who Is the Best Classic Game Show Host? (POLL)