Love him or hate him, there is no denying that Henry Jaglom is an auteur, one that has always made a profit on his quirky, low-budget, stream-of-consciousness pictures, often about loneliness and relationships.

A scion of a wealthy Russian Jewish financier, he began his career in New York theater before moving to Los Angeles where he continued his affiliation with the Actors Studio and was signed as a contract player with Columbia-Screen Gems, working on series like "Gidget" and "The Flying Nun" (both starring Sally Field).

His first foray behind the camera came during the Six Day War (Egypt vs. Israel) in 1967 when he shot a three-hour, 8mm, silent movie on the frontlines. The social gadfly in him had already cultivated friendships with such Hollywood personages as Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, Sally Kellerman, the screenwriter Carol Eastman and producer Bert Schneider of BBS Productions who saw his movie and hired him to help edit Dennis Hopper's "Easy Rider" (1969).

BBS subsequently produced Jaglom's writing-directing debut, "A Safe Place" (1971), a spaced-out, 94-minute fantasy culled from 50 hours of footage, causing critics to decry that unorthodox editing had destroyed all sense of time and yielded a confused mess. Though it boasted performances by no less than Tuesday Weld, Orson Welles and Nicholson and retains a cult following to this day, "A Safe Place" branded him a pariah, and it would be five years before he would make his second film, the Vietnam-obsessed "Tracks" (1976), starring Hopper as a soldier cracking up.

Jaglom is at his best when he combines strong ensemble acting (a trademark of his pictures) with a coherent narrative as in "Sitting Ducks" (1980), a rollicking good comedy about ripping off the Mob, directed with style and a sense of fun. For the most part, however, he has refused to write conventional scripts, rejecting their visual compromise in favor of his distinctive muse, making maddening movies that in the words of David Thomson "might actually bring someone to lay hands on a weapon."

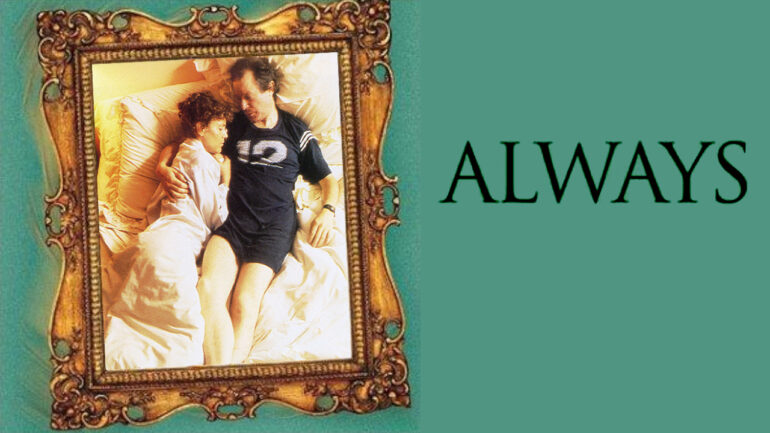

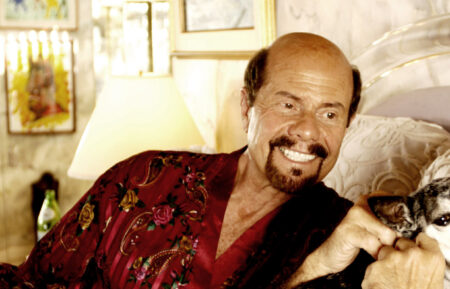

Jaglom's "Can She Bake a Cherry Pie?" (1983), the official US entry at Cannes, starred Karen Black and Jaglom's brother Michael Emil (bringing to his part the same galloping hypochondria and original theories on sex that his "Sitting Ducks" character expressed). Allowing his actors to improvise much of the time, Jaglom got a sometimes uncanny sense of authenticity, as when the neurotic Black tries to make up her mind what to order in a restaurant, but accompanying this blessing was the curse of a slack framework, its scenes dragging on longer than necessary. He fared better with the confessional comedy "Always (But Not Forever)" (1985), a bittersweet account of the breakup of his marriage with Patrice Townsend, starring himself and Townsend. Highly personal and utterly universal, it is one of his most accessible films to date, despite the director's signature wall-to-wall talk and occasional moments when improvisatory inspiration flags.

Jaglom's "Someone to Love" (1987), a seriocomic psychodrama in which the filmmaker calls on his friends to explore why he and they have problems with commitment or finding the right mate, is a loving farewell to Welles (making his final film appearance), his outsized personality in full flavor. Glimpsed briefly at pic's beginning, Welles dominated the entire last section, sensationally responsive, inquisitive, impudent and alive playing himself in a situation that showcased his great mind and conversation. "Eating" (1990), with its predominantly female cast and whimsical understanding of compulsions and fads, brought the director success on the art-house circuit, and "Babyfever" (1994) teamed him for the first time with wife Victoria Foyt, who co-scripted and starred opposite him in yet another docudrama which did its fair share of man-bashing. Leaving the feminist terrain of those two films, he again collaborated with Foyt on "Last Summer at the Hamptons" (1995), a Chekhov-inspired study of a theatrical family headed by Viveca Lindfors (in her last screen role). Polished production values along with engaging performances by Lindfors, Andre Gregory and Jon Robin Baitz helped make his 11th feature a pleasing, passably commercial outing.

Voluble to a fault ("Orson Welles used to say--he talked in paragraphs, I talk in chapters"), Jaglom has created his own larger-than-life character, one which cries out for a better actor than Henry Jaglom on screen. Though he is a professed champion of women, his choice to focus on vain, superficial, obnoxious members of the species in "Eating" painted a shallow portrait of shallow women, and "Babyfever" presented stereotypical females and the specter of the ticking biological clock treated better and in a more timely fashion a decade before. Writing-wise, his partnership with Foyt bodes well, since by Jaglom's own admission she favors a stronger storyline than is his wont. To some, though, "Deja Vu" (1998) exposed her as an underwhelming screen presence, too slight to carry a picture, while others felt it was among Jaglom's best work. His films remain best appreciated by fans of his own peculiar cinema verite, but for more mainstream audiences he finishes a poor second to Woody Allen, whose sense of structure and ability to blend comedy and drama is far superior.