Martin Scorsese

Credits

Martin Scorsese en musique

Self

Show

2024

Martin Scorsese Remembers Powell and Pressburger

Host

Show

2024

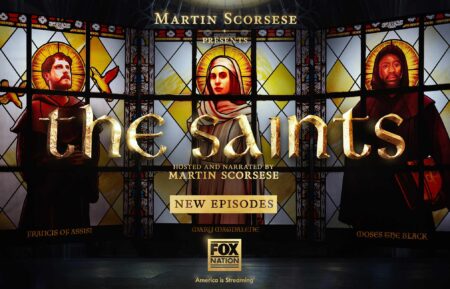

Martin Scorsese Presents: The SaintsStream

Host

Series

2024

Martin Scorsese Presents: The SaintsStream

Narrator

Series

2024

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger

Executive Producer

Movie

2024

Made in England: The Films of Powell and Pressburger

Narrator

Movie

2024

Martin Scorsese Special

Self

Show

2023

Film at Lincoln Center

Guest

Show

2023

Personality Crisis: One Night OnlyStream

Director

Movie

2023

Killers of the Flower MoonStream

Director

Movie

2023

Killers of the Flower MoonStream

Producer

Movie

2023

Killers of the Flower MoonStream

Screenwriter

Movie

2023

MaestroStream

Producer

Movie

2023

The Absence of EdenStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2023

Pet Shop Days

Executive Producer

Movie

2023

The Last Movie StarsStream

Executive Producer

Docuseries

2022

Dreaming Walls

Executive Producer

Movie

2022

The Eternal Daughter

Executive Producer

Movie

2022

Sergio Leone: L'italiano che inventò l'America

Self

Movie

2022

Fragments of Paradise

Self

Movie

2022

Stories of a Generation with Pope Francis

Self

Show

2021

Clint Eastwood: A Cinematic Legacy

Self

Show

2021

In memoriam Charlie Watts

Director

Show

2021

Pretend It's a CityStream

Actor

Movie

2021

Pretend It's a CityStream

Director

Movie

2021

The Card CounterStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2021

MurinaStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2021

The Souvenir Part II

Executive Producer

Movie

2021

Evolution

Executive Producer

Movie

2021

Clint Eastwood: A Cinematic Legacy

Self

Movie

2021

ShirleyStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2020

The Oratorio

Self

Movie

2020

The Irishman: In Conversation

Actor

Show

2019

The Irishman: In Conversation

Director

Show

2019

The MoviesStream

Self

Miniseries

2019

The Current War

Executive Producer

Movie

2019

The IrishmanStream

Director

Movie

2019

The IrishmanStream

Producer

Movie

2019

The SouvenirStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2019

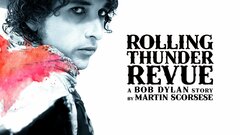

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story by Martin ScorseseStream

Director

Movie

2019

Uncut GemsStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2019

Once Were BrothersStream

Self

Movie

2019

Diane

Executive Producer

Movie

2018

Tomorrow

Executive Producer

Movie

2018

The Sunday Project

Guest

Show

2017

The Breakfast Couch

Guest

Show

2017

No Direction Home: Bob Dylan

Director

Show

2017

Gene Tierney: A Forgotten Star

Self

Show

2017

Martin Scorsese: True Confessions

Guest

Show

2017

The SnowmanStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2017

Long Strange TripStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2017

Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the WorldStream

Self

Movie

2017

John G. Avildsen: King of the Underdogs

Self

Movie

2017

Abundant Acreage Available

Executive Producer

Movie

2017

King Cohen: The Wild World of Filmmaker Larry Cohen

Self

Movie

2017

SpielbergStream

Self

Movie

2017

A Ciambra

Executive Producer

Movie

2017

Drôle de père

Executive Producer

Movie

2017

Andrzej Wajda - Moje inspiracje

Self

Show

2016

Jerry Lewis, clown rebelle

Self

Show

2016

Entrevista BAFTA: Kate Winslet

Guest

Show

2016

Entrevista BAFTA: Martin Scorsese

Guest

Show

2016

VinylStream

Director

Series

2016

VinylStream

Executive Producer

Series

2016

Bleed For ThisStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2016

SilenceStream

Director

Movie

2016

SilenceStream

Producer

Movie

2016

SilenceStream

Screenwriter

Movie

2016

Lumiere!

Self

Movie

2016

Before the FloodStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2016

Free Fire

Executive Producer

Movie

2016

Jerry Lewis: The Man Behind the Clown

Actor

Movie

2016

The Pulitzer at 100

Self

Movie

2016

健さん

Self

Movie

2016

Cine 21

Director

Show

2015

The Late Show With Stephen ColbertStream

Guest

Talk

2015

Dai nostri inviati: La Rai racconta la Mostra del Cinema di Venezia

Self

Show

2015

Close Up With The Hollywood Reporter

Guest

Show

2015

This is Orson Welles

Actor

Show

2015

This Is Orson Welles

Self

Movie

2015

The Wannabe

Executive Producer

Movie

2015

Behind the White Glasses

Self

Movie

2015

Mifune: The Last Samurai

Self

Movie

2015

The Legend of the Palme D'Or

Self

Movie

2015

Pier Paolo Pasolini, maestro corsaro

Self

Movie

2015

Trespassing Bergman

Actor

Show

2014

John Ford at Monument Valley

Self

Show

2014

The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon

Guest

Show

2014

The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy FallonStream

Guest

Talk

2014

Wonderland

Actor

Show

2014

Life Itself

Executive Producer

Movie

2014

Revenge of the Green DragonsStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2014

The 50 Year Argument

Director

Movie

2014

The 50 Year Argument

Producer

Movie

2014

Stars

Actor

Show

2013

Peter Gabriel: Live In Athens 1987

Executive Producer

Show

2013

A Letter to Elia

Director

Show

2013

Trespassing Bergman

Actor

Movie

2013

The FamilyStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2013

Seduced and Abandoned

Self

Movie

2013

The Wolf of Wall StreetStream

Director

Movie

2013

The Wolf of Wall StreetStream

Producer

Movie

2013

Martin Scorsese on Hugo

Self

Show

2011

George Harrison: Living in the Material World

Director

Show

2011

HugoStream

Director

Movie

2011

HugoStream

Producer

Movie

2011

George Harrison: Living in the Material WorldStream

Director

Movie

2011

George Harrison: Living in the Material WorldStream

Producer

Movie

2011

ConanStream

Guest

Talk

2010

Boardwalk EmpireStream

Director

Series

2010

Boardwalk EmpireStream

Executive Producer

Series

2010

The 67th Annual Golden Globe Awards

Guest

Show

2010

...Men filmen är min älskarinna

Actor

Movie

2010

Shutter IslandStream

Director

Movie

2010

Shutter IslandStream

Producer

Movie

2010

Cameraman: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff

Actor

Movie

2010

A Letter to Elia

Director

Movie

2010

A Letter to Elia

Narrator

Movie

2010

A Letter to Elia

Producer

Movie

2010

A Letter to Elia

Writer

Movie

2010

Public Speaking

Director

Movie

2010

The 32nd Annual Kennedy Center Honors

Guest

Show

2009

The Young VictoriaStream

Producer

Movie

2009

Shine a Light

Director

Movie

2008

Lymelife

Executive Producer

Movie

2008

The Key to Reserva

Director

Movie

2007

Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows

Narrator

Movie

2007

Val Lewton: The Man in the Shadows

Producer

Movie

2007

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies

Narrator

Movie

2007

Picasso and Braque Go to the Movies

Producer

Movie

2007

30 RockStream

Guest Star

Martin Scorsese

Series

2006

30 RockStream

Guest Voice

Martin Scorsese

Series

2006

etalk

Guest

Show

2006

Bob Dylan, No Direction Home

Director

Show

2006

The DepartedStream

Director

Movie

2006

Michael Powell

Self

Show

2005

No Direction Home: Bob Dylan

Director

Movie

2005

No Direction Home: Bob Dylan

Producer

Movie

2005

The Cutting Edge: The Magic of Movie Editing

Actor

Show

2004

EntourageStream

Guest Star

Martin Scorsese

Series

2004

Shark Tale

Voice

Sykes

Movie

2004

The AviatorStream

Director

Movie

2004

Cecil B. DeMille: American Epic

Actor

Movie

2004

Lightning in a Bottle

Executive Producer

Movie

2004

FrankensteinStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2004

The Ellen DeGeneres Show

Guest

Talk

2003

Jimmy Kimmel Live!Stream

Guest

Talk

2003

Gangs of New YorkStream

Director

Movie

2002

Arena

Director

Show

2001

Curb Your EnthusiasmStream

Guest Star

Himself

Series

2000

Roberto Rossellini

Actor

Movie

2000

アルマーニ

Actor

Movie

2000

You Can Count on MeStream

Executive Producer

Movie

2000

Talking Movies

Guest

Show

1999

The Daily Show With Jon StewartStream

Guest

Talk

1999

The Muse

Self

Movie

1999

Bringing Out the DeadStream

Director

Movie

1999

My Voyage to Italy

Director

Movie

1999

With Friends Like These...

Self

Movie

1998

The Hi-Lo Country

Producer

Movie

1998

In Search of Kundun With Martin Scorsese

Actor

Movie

1998

Religion & Ethics Newsweekly

Guest

Show

1997

The View

Guest

Talk

1997

Kicked in the Head

Executive Producer

Movie

1997

Kundun

Director

Movie

1997

Access Hollywood

Guest

News

1996

Grace of My Heart

Executive Producer

Movie

1996

Eric Clapton: Nothing But the Blues

Executive Producer

Show

1995

Search and Destroy

Actor

The Accountant

Movie

1995

Search and Destroy

Executive Producer

Movie

1995

A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies

Director

Movie

1995

A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies

Narrator

Movie

1995

A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies

Producer

Movie

1995

A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies

Writer

Movie

1995

ClockersStream

Producer

Movie

1995

CasinoStream

Director

Movie

1995

CasinoStream

Writer

Movie

1995

Extra

Guest

News

1994

Quiz ShowStream

Actor

Martin Rittenhome

Movie

1994

Late Show With David Letterman

Guest

Talk

1993

Mad Dog and GloryStream

Producer

Movie

1993

The Age of InnocenceStream

Director

Movie

1993

The Age of InnocenceStream

Screenwriter

Movie

1993

Naked in New York

Executive Producer

Movie

1993

Amazing Stories: The Movie IV

Director

Movie

1991

Guilty by Suspicion

Actor

Joe Lesser

Movie

1991

Cape FearStream

Director

Movie

1991

Kings Of Ads / 巨匠たちのCF

Director

Movie

1991

Akira Kurosawa's Dreams

Actor

Vincent Van Gogh

Movie

1990

GoodfellasStream

Director

Movie

1990

GoodfellasStream

Screenwriter

Movie

1990

The GriftersStream

Producer

Movie

1990

Made in Milan

Director

Movie

1990

Hollywood Mavericks

Actor

Movie

1990

New York Stories

Director

Movie

1989

The Last Temptation of ChristStream

Director

Movie

1988

Round MidnightStream

Actor

Goodley

Movie

1986

The Color of MoneyStream

Director

Movie

1986

Amazing StoriesStream

Director

Series

1985

After HoursStream

Director

Movie

1985

Pavlova: A Woman for All Time

Actor

Gatti-Cassaza

Show

1983

The King of ComedyStream

Director

Movie

1983

Nightline

Guest

News

1980

Raging BullStream

Director

Movie

1980

CBS News Sunday Morning

Guest

News

1979

The Last WaltzStream

Director

Movie

1978

American Boy: A Profile of: Steven Prince

Director

Movie

1978

New York, New York

Director

Movie

1977

Taxi DriverStream

Director

Movie

1976

Good Morning America

Guest

News

1975

Saturday Night LiveStream

Guest Star

Series

1975

Rockpalast

Director

Show

1974

Alice Doesn't Live Here AnymoreStream

Director

Movie

1974

Italianamerican

Director

Movie

1974

Mean StreetsStream

Actor

Jimmy Shorts (uncredited)

Movie

1973

Mean StreetsStream

Director

Movie

1973

Mean StreetsStream

Writer

Movie

1973

Mean StreetsStream

Writer (Story)

Movie

1973

Boxcar BerthaStream

Actor

Brothel Client

Movie

1972

Boxcar BerthaStream

Director

Movie

1972

Elvis on TourStream

Film Editing

Movie

1972

Street Scenes

Actor

Interviewer

Movie

1970

Street Scenes

Director

Movie

1970

WoodstockStream

Assistant Director

Movie

1970

WoodstockStream

Film Editing

Movie

1970

Bezeten - Het gat in de muur

Screenwriter

Movie

1969

The Dick Cavett ShowStream

Guest

Talk

1968

Who's That Knocking at My Door?

Director

Movie

1968

Who's That Knocking at My Door?

Screenwriter

Movie

1968

The Big Shave

Director

Movie

1967

The Big Shave

Film Editing

Movie

1967

The Big Shave

Producer

Movie

1967

The Big Shave

Screenwriter

Movie

1967

The Big Shave

Writer

Movie

1967

It's Not Just You, Murray!

Director

Movie

1964

It's Not Just You, Murray!

Screenwriter

Movie

1964

What's a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This?

Director

Movie

1963

What's a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This?

Screenwriter

Movie

1963

Today

Guest

News

1952

News aboutMartin Scorsese

New Episodes of ‘Martin Scorsese Presents: The Saints’ Schedule & Preview

How ‘The Studio’ Got Martin Scorsese & More Cameos & Filmed That Epic Oner (VIDEO)

Review

Roush Review: Hooray for Hollyweird in Brilliant ‘Studio’ Satire

‘Cape Fear’: Everything You Need to Know About the Apple TV+ Series

‘The Studio’: Seth Rogen’s a Frazzled Hollywood Exec in Star-Studded Teaser (VIDEO)

10 Best Music Documentaries on Netflix, Ranked

‘Pioneer Woman’ Ree Drummond Has Surprising Link to Martin Scorsese’s ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’

Is TCM Going Away? Legendary Movie Directors Try to Save the Network

‘Gangs of New York’ TV Series in the Works With Martin Scorsese Directing

Keanu Reeves Officially Signs on to Star in ‘Devil in the White City’ at Hulu

‘The Last Movie Stars’ Trailer Unveils Paul Newman & Joanne Woodward’s Love Story (VIDEO)

Keanu Reeves Tapped for Hulu Drama Series From Martin Scorsese & Leonardo DiCaprio

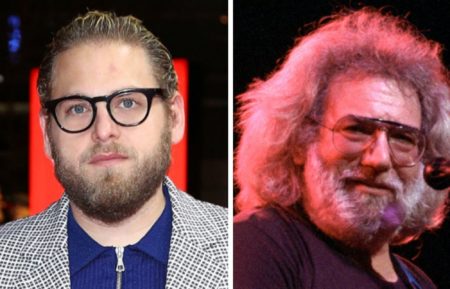

Jonah Hill Is Jerry Garcia in Martin Scorsese’s Grateful Dead AppleTV+ Film

Martin Scorsese’s ‘Pretend It’s a City’ on Netlix Stars Essayist Fran Lebowitz

Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Irishman’ Is an Epic Tale That Was Worth the Wait

Exclusive

‘Lethal Weapon’: Why Will Scorsese Be Seen In A ‘New Light’ This Week?

Prett-ay, Prett-ay, Prett-ay, Pretty Good: Our Favorite ‘Curb Your Enthusiasm’ Guest Stars

HBO Cancels ‘Vinyl’ After One Season

Roush Review: ‘Vinyl’ Is Scorsese’s ‘Life-Altering Rock-pocalypse’

‘Vinyl’ Gets Bobby Cannavale, Martin Scorsese and Mick Jagger Ready to Rock