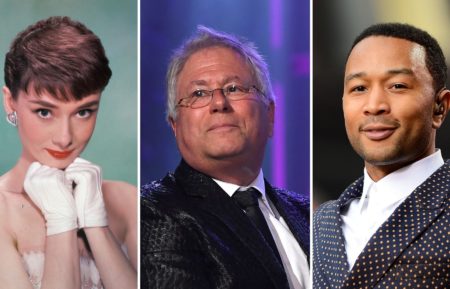

Mike Nichols

Director • Writer • Producer • Comedian

Birth Name: Michael Igor Peschkowsky

Birth Date: November 6, 1931

Death Date: November 19, 2014 — 83 years old

Birth Place: Berlin, Germany

Spouses: Diane Sawyer

After establishing himself as the straight-man half of a popular comic duo with Elaine May in the late 1950s, Mike Nichols became one of the most decorated directors of stage and screen, earning several Tony Awards for his work on Broadway while helming seminal Academy Award-winning films.

Though he began his career as in improvisational comedian and gained a degree of popularity with May, Nichols found his greatest success first on Broadway, where he collaborated extensively with Neil Simon to direct "Barefoot in the Park" (1963) and "The Odd Couple" (1965); both of which earned him Tony Awards for Best Director. He soon moved to Hollywood and directed the controversial "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" (1966), which broke ground for its use of profanity and frank handling of marriage infidelity, and "The Graduate" (1967), which managed to tap into the feelings of isolation and abandonment by that era's youth.

Following a misfire with his adaptation of "Catch-22" (1970), Nichols once again broke ground tackling the subject of sex and relationships with the hit drama, "Carnal Knowledge" (1971). But he soon broke away from Hollywood to focus on the stage, only to return with the acclaimed biopic "Silkwood" (1983), starring Meryl Streep. Following popular hits like "Working Girl" (1988) and "Biloxi Blues" (1988), Nichols' film career hit a precipitous downturn until he directed the surprise hit comedy "The Birdcage" (1996).

On the small screen, he found even more success with the acclaimed made-for-cable movie "Wit" (HBO, 2001) and the extraordinary miniseries "Angels in America" (HBO, 2003), both of which earned their share of critical adulation and awards. After a return to big screen form with "Closer" (2004) and "Charlie Wilson's War" (2007), Nichols proved that he was just as viable as he was when he broke new ground for a previous generation. Still active with stage and screen work well into his 80s, Nichols' sudden death on November 19, 2014 at the age of 83 stunned the film and theater community.

Born Michael Igor Peschowsky on Nov. 6, 1931 in Berlin, Germany, Nichols was raised by his father, Nicholaievitch, a physician, and his mother, Brigitte. When he was four years old, Nichols was given a defective whooping cough vaccine that left his entire body devoid of hair, a condition that precipitated him wearing a wig the rest of his life. Nichols came to America in 1939 when he fled Nazi Germany with his brother, Robert, after their father had set up a medical practice on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Since their mother stayed behind due to ill health, Nichols' father left his two boys with his patients' family, only to see them from time to time while he further established his business. Though the family was reunited when their mother arrived a year and a half later, Nichols' mother and father fought constantly, and seemed assured of divorce if not for their father dying of leukemia in 1942. Meanwhile, Bridgette's descent into depression and hypochondria dragged the family down into abject poverty, and away from the middle-class comfort they had enjoyed when their father was alive.

A perennial outsider due to his initially limited English, Nichols - who was naturalized as a citizen in 1944 and was certified a genius at age 12 - struggled as a student while attending the Dalton School and Walden School in New York. Though able to make others laugh - a trait he received from his father - Nichols was unaware that entertaining people for a living was available to him until he saw Elia Kazan's staging of "A Streetcar Named Desire" when he was 16. He knew from watching that performance, which starred a young Marlon Brando, that he was destined to be involved in theater. By the time he landed at the University of Chicago, Nichols himself had been flung into fits of depression, which led to his firing from deejay duties at the school's radio station on several occasions. But he found solace in the theater, directing his first play, W.B. Yeats' "Purgatory" with Ed Asner in the lead, during his sophomore year. He also performed on stage in several others, including "St. Joan," "La Ronde" and "Miss Julie." Around this time, Nichols met Elaine May, with whom he had a brief romantic entanglement, but also had a long-running professional relationship based on their symbiotic improvisational comedy.

Although they had met previously, Nichols and May did not begin their partnership in earnest until 1955 after he had dropped out of college and briefly studied Method acting with Lee Strasberg in New York. But with no hopes of finding any work, he returned to Chicago and joined the relatively new Compass Players, an improvisatory troupe among whose founders were Paul Sills and May and eventually evolved into the famed comedy group, Second City. Although he performed with others in the group, Nichols' true comedic talents came to full blossom only when partnered with May. The duo shared an effortless chemistry onstage, where they continually challenged one another and enjoyed displaying their verbal wit. Though almost split apart in 1958, Nichols and May went on to enjoy enormous success as the premiere comedy duo of the late 1950s and early 1960s, appearing on "The Steve Allen Show" (NBC/ABC, 1956-1964) and "Omnibus" (CBS/ABC/NBC, 1952-1961), while also making their debut as panelists on "Laugh Line" in 1959.

Over the next several years, Nichols and May saw the culmination of their collaboration with the Broadway production "An Evening with Nichols and May" (1960), which led to a Grammy-winning recording for Best Comedy Performance in 1962. But the strain of performing together began to take its toll that year when the play, "A Matter of Position" - which May wrote, directed and starred in - flopped in Philadelphia. Their partnership and friendship came to a sudden crashing end. Feeling abandoned and without moorings, Nichols was unsure what to do next with his career. So when he was offered a chance to stage the Broadway-bound Neil Simon play "Barefoot in the Park" (1963) he readily accepted. With a cast including Elizabeth Ashley, Robert Redford, Mildred Natwick and Kurt Kaznar, the light romantic comedy became a hit and forged a long-running collaboration with the famed playwright, while winning Nichols his first Tony Award for Best Director. The following year, Nichols directed Simon's seminal comedy, "The Odd Couple" (1965), with Art Carney as Felix Ungar and Walther Matthau as Oscar Madison in the leads. Nichols won his second consecutive Best Director Tony Award, which soon helped break down doors in Hollywood.

Having honed his craft on stage, Nichols moved to the big screen when screen goddess Elizabeth Taylor handpicked him to direct the film adaptation of Edward Albee's blistering portrait of a marriage, "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" (1966). Although he clashed with studio head Jack Warner, who had wanted to make the picture in color, Nichols instead shot the film in stark black and white, while occasionally using handheld cameras to intensify the dramatic tension between a hard-drinking associate professor (Richard Burton) and his taunting, scorn-filled wife (Taylor), who happens to also be the dean's daughter. Tackling the difficult subjects of adultery and alcoholism, while benefiting from the recently abolished Production Code by Motion Picture Association of America head Jack Valenti, Nichols was able to keep most of the so-called offensive language from Albee's play. Though initially faced with an overly concerned Catholic League of Decency threatening to condemn the movie, "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" was kept largely intact and broke ground with its unrelenting use of profane words and phases which had never before been heard on screen. The film itself was a triumph at the box-office and with critics, while earning a near record 13 Academy Award nominations, including Nichols' first for Best Director.

Prior to reuniting with Neil Simon to direct "Plaza Suite" (1968) on Broadway, which earned him his third Tony Award for Best Director, Nichols became an Oscar-winning director with only his second film, the seminal coming-of-age drama "The Graduate" (1967). By focusing on an adrift college graduate (Dustin Hoffman), who is seduced by an older woman (Anne Bancroft), only to fall in love with her daughter (Katharine Ross), the film spoke to the members of a disaffected generation by giving life to otherwise inchoate feelings of alienation and frustration. Ably performed by Hoffman, Bancroft and Ross, and scored by Paul Simon, "The Graduate" became one of the seminal films of the late 1960s alongside "Bonnie and Clyde" (1967) and "Easy Rider" (1969), ushering in a cycle of youth-oriented motion pictures that rejuvenated a moribund American film industry hurt by the splintering of the studio system. The film also earned seven Academy Awards, with Nichols winning the one-and-only statue. Now able to choose whatever project he wished, Nichols opted to film Joseph Heller's complex cult novel "Catch-22" (1970). The overly-detailed feature, however, turned out to be a noble failure, with critics citing Nichols for sentimentalizing the darkly comic absurdity of the original material. Though beautifully shot and well acted by Alan Arkin, Buck Henry, Orson Welles and Jon Voight, "Catch-22" kept audiences at bay with its cerebral remoteness.

Returning to Broadway, he earned his fourth Tony for "The Prisoner of Second Avenue" (1971) and rebounded from "Catch-22" with his next feature effort, "Carnal Knowledge" (1971), a trenchant exploration of sexual politics that solidified Jack Nicholson's star status, proved Candice Bergen was more than a pretty face, and renewed the sagging acting career of Ann-Margret. As he did with "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?" Nichols bucked the MPAA's still-nascent ratings system with the film's frank discourse about sexual mores and overabundance of profane language. Once again, audiences came out in droves, though critics remained split. In between the George C. Scott vehicle "The Day of the Dolphin" (1973) and the period comedy "The Fortune" (1975), with Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson and Stockard Channing - both of which flopped at the box office - Nichols earned yet another Tony Award nod for directing an adaptation of Anton Chekhov's "Uncle Vanya" (1973). Meanwhile, two weeks into shooting "Bogart Slept Here" from a Neil Simon script in 1975, Nichols became frustrated with Hollywood and pulled the plug on the project to leave filmmaking for nearly a decade.

Although he spent some time attempting to jump-start a film version of "A Chorus Line," Nichols largely stayed away from moviemaking and turned his attentions to the small screen, serving as an executive producer on the acclaimed, award-winning drama "Family" (ABC, 1976-80). Following a return to Broadway to direct Trevor Griffiths' play "Comedians" (1976) and serving as one of the producers of the Tony-winning hit musical "Annie" (1977), Nichols earned a Tony Award nomination for another stage success with "The Gin Game" (1977). After stumbling a bit with the comedies "Lunch Hour" (1980) and the short-lived Neil Simon comedy "Fools" (1981), Nichols made a triumphant return to features with the acclaimed biopic, "Silkwood" (1983), which starred Meryl Streep as a nuclear plant employee whose mysterious illness prompts her to conduct an investigation into the plant's malfeasance with its safety procedures. "Silkwood" was not only a commentary on the plight of women in a male-dominated culture, but also depicted how anyone could be dehumanized by a complex system, whether it be the government or big business. The film not only restored Nichols to the ranks of top directors in Hollywood, it also refreshed the career of singer-actress Cher, catapulted Kurt Russell to the ranks of leading men and further demonstrated the seemingly endless talents of star Meryl Streep. It also earned Nichols another Academy Award nomination for Best Director.

Nichols continued his Broadway domination with his fifth Tony Award win for Best Director after his successful staging of Tom Stoppard's "The Real Thing" in 1984. Reuniting with both Streep and Nicholson, he directed the feature drama "Heartburn" (1986), an adaptation of Nora Ephron's caustic roman-a-clef about her failed marriage that once again explored the impact of sexual politics, only this time to less impressive results. His follow-up, "Working Girl" (1988), was a successful satire of the same idea within a corporate setting, and starred a breakout Melanie Griffith as a secretary who finds love and success in the cutthroat world of Wall Street. Following his endearing and light-hearted screen adaptation of Simon's "Biloxi Blues" (1988), Nichols had a successful reunion with Meryl Streep in his take on Carrie Fisher's semi-autobiographical "Postcards from the Edge" (1990), which examined how women coped with working in show business. Though well-crafted and deserving of positive reviews, it was obvious to some observers that Nichols' film career was on a downward slope. But his personal life was on the upswing when he married television news anchor Diane Sawyer in 1988 after spending most of his adult life engaged in a series of failed marriages, including one with singer Patricia Scott.

In the early 1990s, Nichols suffered box-office disappointments with "Regarding Henry" (1991) and "Wolf" (1994), despite high profile leads Harrison Ford and Jack Nicholson, respectively. The former was a somewhat sappy look at a venal corporate lawyer whose life is changed after a shooting, while the latter was a metaphoric character study of the male libido embodied by a man literally turning into a beast. In his first overt reteaming with Elaine May - she reportedly worked as a script doctor on each of his films since they reconciled in the 1970s - Nichols enjoyed a surprise hit with "The Birdcage" (1996), an Americanized remake of the popular French farce "La Cage aux folles." While some gay and lesbian groups were not particularly pleased by what were thought to be stereotypical depictions of homosexual characters, the movie allowed Robin Williams and Nathan Lane to cut loose and give larger-than-life portrayals as a long-standing couple whose lives are upturned when Williams' son visits with his conservative fiancé (Calista Flockhart) and her traditional all-American parents (Gene Hackman and Diane Wiest). Despite a mixed critical bag, the comedy took in over $120 million in domestic box office.

Instead of capitalizing on his success with "The Birdcage," however, Nichols made the daring decision to return to stage acting in the 1996 London production of Wallace Shawn's play "The Designated Mourner," which was preserved on film and released theatrically the following year. Somewhat static and talky, the movie at least allowed audiences a rare opportunity to see Nichols tackle a dramatic role. When he did resume his directorial career, it was with the feature adaptation of the controversial political roman-a-clef, "Primary Colors" (1998). His original choice of Tom Hanks to play a not-too-disguised caricature of Bill Clinton passed on the project in part over concerns on how the lead character was depicted. But star John Travolta had no qualms and accepted the role, delivering one of his more finely-tuned performances. While accomplished, the movie suffered from a case of poor timing, when it was released when Clinton's presidency was in crisis over his sexual liaison with a White House intern. Nonetheless, Elaine May's script was sharp, though overshadowed by the unfolding history. He followed up with the widely panned comedy, "What Planet Are You From?" (2000), which starred Gary Shandling as an alien who comes to Earth in order to impregnate a human woman, only to discover the task's difficulty. Both a critical and box office failure, the movie was quickly forgotten after being relegated to cable outlets and video store shelves.

Nichols roared back by collaborating with "Primary Colors" lead Emma Thompson on a small screen adaptation of the Pulitzer-winning drama "Wit" (HBO, 2001). Focusing on an uptight, sardonic professor (Thompson) who contracts terminal cancer, the film version was a brilliantly acted ensemble piece, anchored by Thompson's luminous performance. Nichols served as co-executive producer, co-author of the teleplay with Thompson and director, while earning Emmy Awards for his direction and as producer of the Outstanding Made for Television Movie. A remarkable achievement for any medium, "Wit" demonstrated that when given the right material, Nichols was still able to rise to the occasion. Anticipation ran high for his next project, the six-part HBO adaptation of Tony Kushner's charged epic of interwoven AIDS-related stories, "Angels in America" (2003). With a stellar cast led by Al Pacino, Meryl Streep and Thompson, the film was among the most highly praised television presentations of the year. Nichols was duly rewarded with two Emmys - one for Outstanding Directing for a Miniseries, Movie or a Dramatic Special; the other as a producer for Outstanding Miniseries. Also that year, he won the Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Movies for Television the same year he was given a Lifetime Achievement Award by the guild.

Nichols returned to feature films when he directed the highly literate, often romantically brutal battle of the sexes, "Closer" (2004), a tense, charged throwback to his earlier films "Carnal Knowledge" and "Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?," which was based on Patrick Marber's play about a pair of couples (Jude Law, Natalie Portman, Julia Roberts and Clive Owen) who become messily intertwined with one another. Although the film garnered mixed reviews, some raved about Nichols' return to form. Away from the screen, Nichols proved that he remained a potent force in the world of legitimate theater, winning his sixth Tony Award as Best Director in 2005 for helming the enormously popular and critically hailed Broadway production of "Spamalot," culled from the 1975 film "Monty Python and the Holy Grail." He next produced "Whoopi, the 20th Anniversary Show" (2005), which marked comedian Whoopi Goldberg's return to the stage and earned Nichols a Tony nomination for Best Special Theatrical Event. Back on the silver screen, he directed "Charlie Wilson's War" (2007), which starred Tom Hanks as the freewheeling titular Congressman from Texas, who finds his mission in life by arming the Mujahideen warriors in Afghanistan fighting the invading Russian army. He returned to Broadway with a revival of Clifford Odets' "The Country Girl" starring Morgan Freeman and Frances McDormand the following year.

In June 2010, Nichols was honored with an American Film Institute award for Lifetime Achievement and feted in Los Angeles by some of the biggest names in the business, including former co-workers Harrison Ford, Meryl Streep, Julia Roberts and Cher. The following year, he served as executive producer of "Friends With Kids" (2011), an ensemble comedy-drama written and directed by Jennifer Westfeldt and starring Westfeldt, Maya Rudolph, Adam Scott, Chris O'Dowd, Kristin Wiig, and Wesfeldt's partner Jon Hamm. A critically-acclaimed revival of Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman," a play which had made a strong impression on Nichols as a young actor, won him a Tony in 2012. He then directed a revival of Harold Pinter's "Betrayal," starring Daniel Craig and Rachel Weisz, in 2013. Nichols' final screen credit came as the executive producer of "Crescendo! The Power of Music" (2014), a documentary about a Central American youth orchestra program.

Mike Nichols died suddenly of a heart attack on November 19, 2014, at the age of 83.

Credits

Becoming Mike Nichols: El Retrato de un Artista

Becoming Mike Nichols

Everything Is Copy

Crescendo! The Power of Music

Friends With KidsStream

The Last Play at Shea

Charlie Wilson's WarStream

CloserStream

Angels In AmericaStream

High School ReunionStream

Angels in America

Angels in America

Regarding Henry

WitStream

WitStream

WitStream

What Planet Are You From?

What Planet Are You From?

Primary ColorsStream

Primary ColorsStream

The ViewStream

The Designated Mourner

La Casa de las Locas

The BirdcageStream

The BirdcageStream

Nichols and May: Take Two

Inside the Actors Studio

WolfStream

The Remains of the DayStream

Regarding HenryStream

Regarding HenryStream

Postcards from the EdgeStream

Postcards from the EdgeStream

Biloxi BluesStream

Working GirlStream

The Longshot

HeartburnStream

HeartburnStream

SilkwoodStream

SilkwoodStream

Gilda

Gilda Live

Dos Pillos Tras la Heredera

The Fortune

The Fortune

The Day of the Dolphin

Carnal KnowledgeStream

Carnal KnowledgeStream

Catch-22Stream

The GraduateStream

The GraduateStream

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?Stream

Laugh Line